In the fall of 2023, I felt an urge to visit the home of my upbringing to stand in the garage and gaze at some marks I had made on the wall during the latter part of my youth. I had stumbled upon some cans of black and white gloss paint resting on the floor, alongside a slim house-painting brush, and I vividly recall how, once the initial dab transformed into a line, I found myself quickly absorbed in the satisfaction of creating more lines consecutively. I sketched a figure of a woman in a flowing dress, perhaps resembling a kimono, adorned with a wide belt or obi, and her hair styled high. And when it was complete, I paused.

I doubt its quality as a painting, but it had the right form; it conveyed emotion. Moreover, no one voiced any complaints. Despite the garage being connected to the house, it was perceived as my father’s territory, and it appeared he was unfazed by my brushwork on the wall, though he might have had concerns about the brush’s condition. He might have asked, “Why did you do that?” which would have been enough to halt my creative efforts, yet as far as I can recall, there were no significant consequences for my leisurely grafitti that afternoon.

At that juncture, the garage was cluttered with stray bits, and even though he puttered around, my father didn’t utilize the space much anymore. In the early years of his marriage, he nearly furnished the house himself from the workbench. He crafted three chests of drawers from solid, light oak, an entire living-room set, and a hall table with parquetry inlay. Five children later, he was piecing together a wardrobe from MDF; his passion for fine craftsmanship had evidently diminished. He could also afford a car which took up space in the garage during chilly weather, with its large, mint-green hood nestled under the cupboards and shelves stocked with tins of nuts and washers, and rows of tools, their wooden handles darkened from use.

One morning, amid the long autumn while my mother was passing away, I awoke with the vision of my garage painting in mind, along with an urge to verify its presence. I hadn’t contemplated it in ages, yet it appeared so vividly in my mind, and the desire for confirmation lingered throughout the day. I wanted to go home.

Chances are, it was a reproduction of something I had encountered. When I delve into my memory for the original image, a picture emerges from a beloved book I cherished at age 11, the Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology—a splendid, hefty, ink-scented Christmas gift that still resides on my shelf. There, beyond the Greek statues and Egyptian hieroglyphs, I spot a Chinese ink drawing of Ch’ang-O, the moon goddess. So, it wasn’t a kimono after all. The broad belt I recalled was, in reality, a wide sleeve, yet the shape, the elevated hair, and the drape of fabric in her lengthy skirt are unmistakably the same.

This wistful sensation that I couldn’t revisit the garage wall of my childhood was entirely constructed, for I could easily hop into my car and arrive there in half an hour. The key to the front door hung from my keyring. There was absolutely nothing preventing me. However, the house had stood vacant since my mother moved into care, imparting an air of privacy; it felt neither empty nor occupied. She had lingered between life and death for many months, and as time dragged on, her home became increasingly off-limits. All trips now culminated at her bedside. Turn left, not right.

Even when she was still residing there, I struggled to navigate freely within the house. She would call me back from the kitchen when I attempted to boil water, asking me to repair something, accomplish something, check on her, converse with her, talk more, share my updates, assist her in standing. This blend of urgency and restriction had presented issues for several years. She required constant attention. Professional assistance was supplemented by her children in a schedule that was shared every Saturday morning in the family chat with a sense of foreboding. Countless Saturdays passed. Countless weeks. The marital bed, where my father slowly passed in 2016, was now occupied by a series of gentle strangers, leaving the house feeling cared for yet somewhat stripped of its personal touch. The rooms were emptied for various hospital visits and filled again with grandchildren and great-grandchildren on birthdays we never anticipated she would witness – 92, 93, 94. She transitioned from hospital care to recovery care and ultimately into residential care. There arrived a moment when we understood she would not return home, alive.

“Does she still recognize you?” People worried about this on my behalf, and I wished to respond “probably” or “yes,” she recognized me on some profound level. Yet, I also wanted to express that “being known” was hardly the focus for me. She had transformed into “our” mother; less mine than a communal obligation in which I shared. Within all this effort, I remained, as always, her least responsible child, yet I was still present.

“Is she still herself?”

Either you comprehend the responsibilities of elder care or you cannot begin to fathom it. These discussions (many refrained from asking at all) carried notions about identity that I relinquished over the prolonged years of her decline. At the furthest point of her advanced age, she could barely maintain a sentence, let alone hold a conversation. By then, our concern was less for her personality and more for her existence, which needed honoring as her abilities diminished.

“Yes, yes. She is still herself.”

And she was. She remained in her space, surrounded by her family who did whatever she requested, aiding in the preservation of her identity. During Covid, I found her very demanding, yet over time, she softened into forgetfulness, and the final years felt like a reclamation of childhood affections for me. “Of course I know you. I’ve known you since you were this tall,” she once expressed, genuinely delighted. I would enter her room, and we were delighted to see each other, every single time.

For some inexplicable reason, I felt an urge to be by her side the week she died, and so I found myself alone with her at the end. Her labored breathing eased, and I pondered whether someone unconscious could also drift off to sleep. By the time I noticed she was slipping away, it was over.

The following morning, the house was bustling with people as we organized the funeral and the wake. The kettle was brewing, the wifi was functioning, and the television displayed the draft memorial leaflet via Chromecast. The place appeared ordinary, tidy. The carpets, predominantly green, were vacuumed by a grieving grandchild, and it was starting to feel like the house I had always known.

My parents had settled into this humble bungalow in the suburbs while the final houses on the street were under construction. The cul-de-sac gradually filled with youthful married couples like themselves; the men went to work, the women visited each other’s kitchens, and the children played on the road outside. Our mother was the last of that generation to pass away. The neighbors’ children were now reaching retirement age. The configuration of our home was either identical to, or mirrored that of, their own childhood surroundings, and when they came for the wake, they survey the rooms with aged faces yet youthful eyes.

A few days after, I went to retrieve some dishes and found the house quiet and still, laden with remnants. Every spot my gaze fell upon became a still life. On a crocheted doily on my mother’s nightstand, a paperback copy of Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner, paired with rosary beads and a Post-it note inscribed in her handwriting.

If not now When?

If not here Where?

If not you Who?

In the hallway, on the oak chest of drawers crafted by my father, lay another embroidered piece of linen, a crystal vase holding large silk flowers, the phonebook with numbers scrawled inside the cover, either crossed out or marked multiple times as older individuals passed away, or younger ones moved abroad, returned, or acquired mobile phones. Next to the landline was a key for the postbox on the outside wall, its tag bearing a picture of her first great-grandchild as an infant. There was her spectacles case, an upright decorative item with a fake sheepskin lining, and it seemed startlingly particular, this object she had selected, used, and overlooked, daily for years.

The stillness was palpable. I took some photographs to distract myself, and this felt akin to theft. Furthermore, the photographs appeared insignificant when I viewed them on my phone. They failed to capture the emotion, nor could they represent the earlier versions of the house I saw in every direction. There was a round window in the living room that I woke to when it was the girls’ bedroom. Back then, the sill housed a porcelain statue of the Infant of Prague, which eventually became a headless version, replaced by a Belleek vase shaped like an owl, which then vanished completely. Upon inquiring about the owl, my mother responded, “I threw it against the coal-house wall” (the vase was a gift from her sister, who could be rather bothersome), but years later, it reappeared: she either purchased another or the destruction story was a jest. I don’t recall any fragments. The owl stood there presently, in need of dusting.

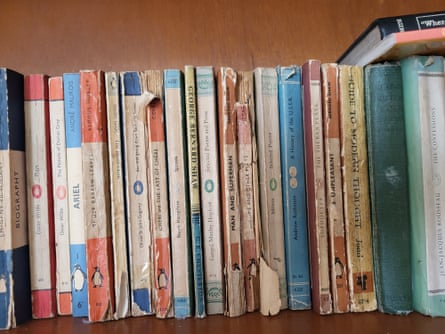

The markers of my mother’s existence, the items that mattered most to her, were keys, each hung on its designated hook or tucked away; also the remote control, stove knobs, and electrical sockets—all necessities that required toggling on and off, because this sanctuary was, for her, charged with potential disaster. I attempted to concentrate on the peculiarities of the place: a practical piece of wood my father affixed to prevent the sliding door from crushing small fingers. A book in her bedroom by Sartre, adorned with a prominent quote on the cover, “I loathe my childhood and all that remains of it …” Another in the dining-room shelves titled Three to Get Married, which did not address polyamory but instead the notion of God’s presence in every relationship. In an act of atonement, I dusted and repositioned a studio portrait of my mother which my father had placed where he sat reading his newspapers. Taken in her twenties, the photo portrays her as a gentle and unadorned beauty.

For a period, I refrained from returning. I’m uncertain if any of us did. The Christmas that followed was quiet and unburdened, perhaps for the first time in my entire life, devoid of family obligations.

In January, I contacted a sibling executor and specified that all I desired were my father’s English-Irish dictionaries, nothing else, not one single item. My sibling executor remarked that while that was agreeable, there would be a method, possibly involving stickers, and I immediately began to resent everyone. Later, I felt guilt. Nothing had been taken from me – nor could it be. I had no real interest in the dictionaries, although for one serious moment, they seemed the perfect remedy for my sorrow. They would fill my void precisely.

In early February, the siblings undertook the first sorting of clothing and linens. We pulled out blankets knitted and crocheted by women now gone, distributed scarves, sifted through my mother’s button collection, recalling the garments they had adorned. I recognized one from a lovely purple-and-pink tweed coat I wore at six. I remembered how the sight of my bare wrists as I outgrew it seemed to infuriate my mother one morning on my way to school. This was around the time our grandmother died, and afterward, she mourned intensely. I spotted a blue button from my confirmation outfit. A sister and I disagreed on the shade of the linen mix, with no way to verify, as family photographs were entirely in black and white. Additionally, my confirmation images were left undeveloped in our father’s camera, for reasons unknown that I always presumed must have been secretly sorrowful.

We are a diligent bunch, the Enrights. Also principled, dependable, and system-oriented. There are no conflicts and much apparent proficiency. Signs are affixed to the doors of various rooms. Stickers come into play. Despite all this, we become muddled, distracted, we misplace things, as if the house were playing tricks on us, with rooms devolving into unstable areas.

“Where are my keys?”

“Could someone please ring my phone?”

I open the least striking, most unremarkable door in the most inconspicuous piece of furniture in the house and uncover a cloth envelope brimming with letters. We gather bit by bit in the sunroom as a sister browses through and reads snippets aloud. I regret to inform you that Eileen passed away this day at 8pm. Some long-gone relative penning about another’s demise to someone else, also long departed. A letter to my father from his father, composed in the 1940s.

My sister picks up yet another letter. This one from my mother to my father, written pre-marriage, My dear Donal, I pray you are safe and well and not overly straining your nerves or your temper. This revelation is altogether new – the father we knew lacked any temper, he was the mildest of men. I have been pretty much fed up since you departed. On Monday, I felt it worst of all. It is a love letter, filled with longing disguised as complaint.

She has filled her week with activities to cope with the solitude. A really nice photo of them together buoyed me morning and night as it sat beside my bed. Yet, What do you think I did today but knocked it over and broke it. Was I mad? She tries not to fret about him while on the road, but worry still gnaws at her. I hope I am not dwelling too much in this letter on safety … I’ll say a quick prayer now and then just the same.

Love manifesting as loneliness, as minor catastrophe and comical irritation, love converted into anxiety turned into piety. The revelation stands that these emotions existed before we, her children, became their source. Moreover, her sincerity and genial nature are vividly present on the page. She was undeniably herself, throughout.

On this, the initial day of clearing, I express a desire to have some snowdrops from the garden, and a sister responds, “Oh do, take them now.” Hence, I procure my father’s shovel and find its sharp blade exceedingly adept, allowing me to dig another patch of turf to fill in the gap, ensuring no one would discern my presence. I place the shovel in the car to take with me. It stands tall, akin to him, and the wood holds the memory of his laboring hands. That is all I wish, I think. I am finished.

However, when the time arrives for the division of belongings a few weeks later, my stickers grace the rooms, landing on treasures I find hard to believe are uncontested. Five cut-glass whiskey tumblers (one with a chip), a bottle of Powers Whiskey I gifted my father in 2010, which my mother insisted on saving for her own wake. A scarf I returned from my travels that she didn’t favor but wore regardless to an official literary event where she cornered Enda Kenny, our then Taoiseach, and conversed with him in Irish at length. A butter dish I have no use for. Champagne saucers that may have never seen champagne, although I did consume jellied desserts from them every Christmas Day. Additionally, her tin of buttons and two final, undeveloped rolls of film.

I do not take his magnifying glass. I cannot take, nor bear to discard, her rolling pin. None of us are able to. I will repeatedly falter in sorting or discarding these belongings, as will my siblings. This includes a mountain of old documents, all possessing significance: their travel itinerary or diaries from the year they journeyed across America, antique photographs, the belongings of a friend who passed away without relatives in the 1970s, whose keepsakes were stored in a box in the attic due to their overwhelming sadness.

Everything must be seen and experienced before it can be recycled, shredded, or ultimately discarded. We must honor and grieve. We must absorb the history embedded within each item, allowing it to transform into mere waste. This alchemical process is profoundly exhausting. Each decluttering day, the same haze descends. Beneath the items I cannot part with lies the baggage my parents were unable to relinquish. My father cherished a newspaper clipping. He kept misdelivered mail, which makes perfect sense to me—how could one discard something that isn’t theirs? That would be unlawful. I open an untouched envelope addressed to a stranger and discover a 60s postcard depicting overly enthusiastic African dancers, with a message on the back from a missionary priest. He declares that all is well. This is reassuring.

I dispose of it.

I discard it all.

Within my father’s numerous files, I find a rugged parcel that, upon careful unwrapping, unveils a collection of seashells from a beach visit 60 years prior. In the tiny bedroom, his trove of VHS tapes encompasses every television appearance I ever made. I stumble upon my old school notebooks.

The process of clearing is sluggish.

On one of these days, I confront the garage, which is now filled with the plastic and aluminum remnants of old age, all intimate and dreadful: a plastic shower chair, a commode, a variety of canes. The calendar on the cabinet shows October 1997. And there upon the wall is my painting of the moon goddess. Part of it has been smeared over with thin paint during brush cleaning, yet some can still be seen: the wide sleeve and skirt, and the white and grey drapes of fabric. I couldn’t be more disillusioned. It is not beautiful, after all. It simply isn’t. It amounts to nothing.

Months later, once the house is wholly stripped bare, I reflect, you know, for an 11-year-old, it wasn’t half bad.

The images from the undeveloped film arrive via email from the camera shop. Most appear splotched and faded, yet among them are two family photos and some landscape shots from the year we camped in Kerry and enjoyed the rollercoaster at a fair in Tralee. The other roll was damaged by a gap in the back of the camera; that indeed explains why he ceased taking photographs, not due to sadness or disinterest. A light leak obscures my 11-year-old face, but my confirmation attire is visible, buttons that are much nicer than the one I discovered in the box. I am clad in summer gloves, and sporting a ribboned pin of the Holy Ghost in dove form. Crowned with a long-forgotten, handmade pillbox hat, the blue hue of which will forever remain indeterminate.

A second image depicts a faded photograph of my face, revealing an unfamiliar expression—not the open, unrefined smile of my childhood, but something more calculating and curious about mischief. The future teenager emerges, seen for the first time. There I am.