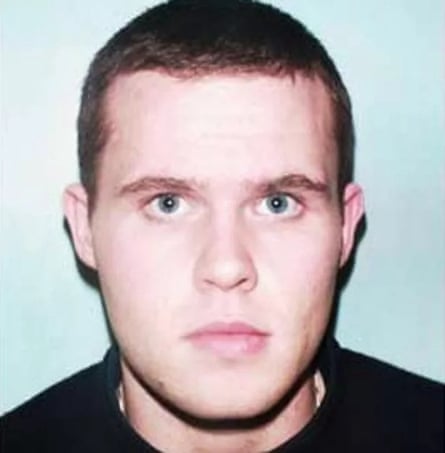

Jack McAvoy occupied a detention cell at Belmarsh prison, biding his time to be processed, scheming his escape. It was the year 2007, he was 24 years old, and had been detained for firearms charges and plotting a theft. He understood he was facing a significant time behind bars, having previously spent three years for illegal firearm possession. He recognized that his sole chance to flee was through the hospital wing, thus he spent the day fabricating stories to the guards, claiming to have suffered a concussion during his arrest. When the holding cell doors opened, he anticipated that would be his path. Instead, he was shackled and taken to a high-security unit (HSU).

Upon his arrival at the unit, the reality of his predicament struck him hard. “I thought: ‘I’m not going to see daylight for a long time.’”

The Belmarsh HSU functions as a prison within a prison. Accessing it necessitates a brief bus ride through the main facility, past a specialized gate and surrounding wall. There’s an airlock with doors that are remotely controlled to avert hostage situations. The spur in the HSU is compact, containing roughly eight cells, with low ceilings and fluorescent lighting. “We referred to it as the submarine,” McAvoy recalls. “There’s no genuine natural sunlight. One section has no windows at all. It’s incredibly claustrophobic.” An exercise yard existed, but was obstructed by security wire. McAvoy’s fellow inmates included the radical preacher Abu Hamza and the unsuccessful 21/7 bombers.

“This is the end of the world,” one of the prison governors advised him. And it truly could have been. Yet for McAvoy, it marked a beginning: the initial unexpected step toward becoming the prolific endurance athlete he is now. By the time he was released in 2012, after nearly a decade in confinement, he had set three world records and seven British records in rowing – all achieved from within the gym walls of the prison.

McAvoy was born in London during the early 80s, raised by his mother along with his sister and five aunts. He never got to know his biological father, who passed away a month prior to his birth. McAvoy’s mother was employed as a florist. They struggled financially, “but she did everything within her power to ensure her two children had all they required.” McAvoy was an active child, occasionally mischievous. His childhood home was adjacent to Crystal Palace Park in south-east London, where he would build camps with friends and catch fish from the lake.

At the age of eight, McAvoy’s mother introduced a new partner, Billy Tobin, into their lives. Aside from an occasional uncle or cousin, Tobin marked the first consistent male presence in McAvoy’s home. Tobin was an armed robber. This fact eluded McAvoy at the time; he merely found him mesmerizing. He reflects on Tobin’s charm, his polished black shoes, dark trousers, and shirt. “Even at a young age, I could recognize that the clothes he wore were quite costly.” When Tobin departed that day, he affectionately patted McAvoy’s head, praised him, and handed him a £20 note (the first instance of McAvoy holding paper currency). Tobin subsequently became McAvoy’s stepfather. “It was a profoundly significant moment.” McAvoy was an ambitious teenager. “I grew up during Margaret Thatcher’s era. It was all about ‘me’. I aspired to own British Telecom. I wanted to be a billionaire.”

As he matured, McAvoy became increasingly aware of the criminal ties within his family. His uncle Micky McAvoy was involved in the heist of the Brink’s-Mat robbery – one of the largest robberies in British history, which resulted in £26m worth of gold, diamonds, and cash being stolen from a Heathrow Airport warehouse. Aged 12, he watched the film Fool’s Gold, a 1992 television production based on the robbery, which featured Sean Bean portraying his uncle. “It was a pivotal moment in my childhood,” he recounts, “Sean Bean sitting atop £26m in gold bars and it being glamorized.” It wouldn’t be long before he got involved in his stepfather’s illicit world – at 14, Tobin assigned him the responsibility of guarding duffle bags filled with £250,000 in cash on their kitchen table until someone came to retrieve it. He received £1,000 for this task.

At 16, McAvoy dropped out of school and acquired a firearm. Tobin was outraged – he wanted to steer McAvoy clear of recklessness. He seized the gun and took his stepson under his guidance. “I didn’t have peers my own age,” he states. “From the age of 15, I surrounded myself with men in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.” They were all affluent criminals. “I sought to immerse myself in their company to learn from their experiences and comprehend how that world functioned.”

Tobin assigned McAvoy to various tasks, including tracking cash-delivery vans, identifying targets, and relaying information within the network. Although McAvoy was introverted and struggled with communication, Tobin taught him how to be confident. He also instructed him never to trust women, to avoid speaking in homes due to potential surveillance, and to have faith only in close companions. He emphasized never to exhibit vulnerability – and to have disdain for authority. Anyone connected to the system – the government, judges, law enforcement – was seen as an adversary. “There was this consistent message of anti-authority and how corrupt the system was. I obviously didn’t recognize that I was absorbing all of this.” A strict moral code prevailed among them as well: “You don’t harm women, children, or the elderly.”

McAvoy was fully aware that incarceration was a likely outcome in his profession. “It’s always on your mind, but you believe you’re going to be the exception who leads that Hollywood lifestyle, right? You’re going to be the one who escapes and lives happily ever after.” He was aware of being under police observation – he discovered tracking devices on his vehicle – and always maintained a heightened sense of surveillance awareness. “You would occasionally notice the same individual multiple times.”

McAvoy’s initial arrest occurred at 18, after police interrupted a robbery valued at approximately £250,000. He led law enforcement on a pursuit down the motorway, disposed of the vehicle (along with his firearm) in south-east London, changed into shorts (as he was advised to wear them for convenience when fleeing), and continued on foot. After jumping over garden fences, he believed he had evaded capture. He located a phone box and called a friend, but soon found himself surrounded by armed police and taken into custody. McAvoy received a five-year sentence for firearm possession. He served three years, including one year in solitary confinement.

His second arrest took place in 2005, two years following his release. At 22, McAvoy was en route to rob a cash-delivery van when he spotted an unmarked police vehicle approaching. It was a setup. The authorities had been monitoring McAvoy and his associates for an extended period. As armed personnel emerged from three police cars, McAvoy accelerated away, navigating through the streets of south London.

“I recall an internal monologue, thinking: ‘I’m not going back to prison.’ And honestly, I was entirely ready to die in that moment to escape them.” After mounting the pavement and colliding with a lamppost, McAvoy abandoned the vehicle and sprinted on foot, striving to outrun the helicopter overhead. He reached a dead end. The law enforcement closed in. They aimed their weapons at him. “At that moment, I genuinely thought, ‘I’m finished’,” he reflects.

McAvoy admitted guilt to one charge of conspiracy to commit robbery and one charge of possession of firearms with the intent to commit robbery. He was moved to Belmarsh three days later.

McAvoy received a discretionary life sentence. His uncle Micky, who served 16 years for involvement in the Brink’s-Mat robbery, imparted some wisdom: stay connected to reality. “I made it a point to keep myself grounded,” he mentions. He would listen to the radio and catch up on news. “I avoided getting involved in prison politics. I would think: ‘This is not my life. I just wish to escape this place as soon as possible and reclaim my life.’”

His mother visited him once. It took several weeks for the governor to authorize the visit. She drove to the prison, then took a bus to the HSU, where she sat in a booth separated by armored glass. A prison officer was seated behind McAvoy with pen and paper. They were prohibited from speaking in code, covering their mouths, and there were cameras directed at both of them. Abu Hamza was in the adjoining booth receiving a legal visit. McAvoy spent 90 minutes with his mother. He recognized it was a profoundly traumatic experience for her. “I made a resolution that day – I returned to my cell, and she didn’t see me until the day I was released, nearly eight years later.”

Initially, he struggled to grasp why he was housed alongside terrorists. He voiced his concerns to a visitor from the Ministry of Justice, who informed him that they didn’t want to provide him with any opportunity to flee. “You get regarded as a worthless individual,” McAvoy states. “There was never any conversation about rehabilitation or making headway in life positively. It’s just, that’s who you are, and that’s what you’ll be for the rest of your existence.”

McAvoy claims he was obsessed with setting goals. He read extensively and maintained his physical health by engaging in what he termed “cell circuits” – numerous sit-ups, step-ups, and push-ups. He felt at ease in his solitude and was never bored. “I never faced any mental health [challenges] in there,” he states. “I never let my thoughts wander too far into the future.”

After two years at Belmarsh, he was moved to Full Sutton, a maximum-security facility in Yorkshire, and later transferred to Lowdham Grange, a category B prison in Nottinghamshire. Initially, McAvoy’s objective was straightforward: comply with the system until he could transition into a low-security prison, then escape. “I thought that the second they gave me the chance in a semi-open prison, I’m out. Off to Europe, living the criminal lifestyle. That was my mindset.”

However, three years into his incarceration, everything shifted. A close friend, Aaron, perished in a vehicle accident in the Netherlands while attempting to flee after robbing an ATM with a couple of partners. The following night, McAvoy watched CCTV footage of the incident on the news.

“That was the lowest point I believe I’ve ever experienced,” he reflects. “It provided me with a substantial reality check regarding my existence and what I was doing.” It served as a grim catalyst for transformation. “I felt adrift. I had no idea what I wanted to achieve or where to go. I was ensnared in this physical environment and the need to break free was pressing. I wanted to distance myself from the other prisoners. My desire was for my life to take a different direction.”

McAvoy frequented the prison gym, where he noticed another inmate rowing on a machine, who had exceeded the typical gym time. Upon inquiry, the prisoner disclosed he was rowing 1 million meters for a children’s charity. McAvoy requested permission from the gym officer to undertake a similar challenge. That event marked the inception of his rowing journey.

“I lacked any understanding of what I was doing or the proper technique. But on that machine, it felt as though I had forged a portal that transported me out of the prison. Everyone left me in peace. No one approached me. I was deep in my own thoughts, and it became a meditative experience. It was very rhythmic.” He now suspects he had tapped into the runner’s high. “It felt like the machine transformed into an extension of my body.”

McAvoy completed the first million meters in one month. He expressed interest in another sponsored row, followed by more. Someone proposed he replicate the rowing distance of the Atlantic Ocean – 5,000 km. “I thought it would be a meaningful achievement.” One evening, nearing the completion of his latest charity work, he resolved to push through a challenging 10,000 meters. A prison officer, Darren Davis, noticed his outstanding performance. “A few days later, he returned with all the records established for indoor rowing machines.”

In just over a year, McAvoy shattered three indoor rowing world records along with seven British records. He annihilated the previous fastest marathon record by seven minutes, took the longest continuous row title (45 hours), and gained the record for the maximum distance covered in 24 hours (263,396 meters).

Initially, McAvoy held a disdain for Davis. He had no interest in reform and perceived the guard as just another instrument of the system. But Davis’s steadfast support of McAvoy’s athletic pursuits eventually endeared him to the prisoner. “He recognized my potential and instilled in me the belief that I could achieve something greater with my life.” Davis was present for all of McAvoy’s record-setting attempts inside the prison. He would bring a chair and remain with him during long rowing sessions, coaching him along the way.

“He transformed my life in prison,” McAvoy professes. “He had no ulterior motives; he simply wanted to help me. His kindness was grounded in the intrinsic human desire to assist another without seeking anything in return.”

Today, Davis stands as one of McAvoy’s closest friends. “I knew when my friend died that I would never again resort to crime, and I can’t predict where that path would’ve led me,” McAvoy reflects. “However, I wouldn’t have the life I possess today if Darren hadn’t believed in me and provided the opportunities to harness the talent he recognized in me.”

During his incarceration, McAvoy began studying for a personal trainer qualification. Upon his transfer to Sudbury, a category D prison, he secured a position as a trainer at a Fitness First gym, taking a 7am bus from the prison six days a week. While training clients, he dedicated time to studying endurance athletes. Nine months later, in 2012, he was granted parole and released from prison. Almost eight years had elapsed since his second conviction. The first action he took upon leaving prison was to visit Aaron’s grave.

McAvoy had one aim: to become a professional athlete. Aware that time was not in his favor at age 30, he began preparing for a triathlon: he joined a rowing club, self-taught swimming through YouTube, purchased his first bike, and learned to ride it. He has since made a name for himself as a formidable endurance athlete, completing numerous ultramarathons, triathlons, and Ironman events.

“My time in prison, along with years of solitude and isolation, certainly shaped me as an athlete,” he states. “I’ve endured segregation… Now, everything else feels like a privilege. A luxury.”

The event that resonates the most for him is his inaugural Ironman in 2013, in Bolton town center. He would watch the competition while imprisoned, and after his release, he had only six weeks to train for it. “I recall feeling an immense sense of accomplishment,” he reflects. “I would consider it one of my best performances given the limited preparation. And Darren was at the finish line.”

Initially, McAvoy refrained from disclosing his past to anyone he met through training. However, as whispers circulated within his rowing club – where had this impressive individual been all this time? – people began to research him. He chose to recount his experiences through a blog. Initially, he feared backlash. That people would claim he had done many wrongs and didn’t deserve his present life; that he shouldn’t be idolized. But he is careful not to romanticize his previous life. In 2016, he published his memoir and has received numerous offers to adapt his life story into a film. However, he has consistently declined.

You can sense he aims to be the mentor he lacked during his formative years when Tobin entered his life. “I have no doubt, had a different individual come into my life – Richard Branson, an Olympic champion, whoever – during my youth, my path would have taken a very different trajectory.”

In 2023, McAvoy’s uncle Micky passed away. The last encounter McAvoy had with his stepfather occurred in Belmarsh’s reception area in 2002. During transfer, McAvoy recognized his voice and called out to him. They exchanged greetings and persuaded the police to allow a brief reunion. They opened Tobin’s cell. “I recall seeing him that day in the reception area. He was handcuffed to a prison officer half his age,” he recounts. “It was surreal. Reflecting on my childhood when I initially saw him, through the years spent together and the activities we did, to then witness him in such a state in prison, appearing truly frail. He had entirely lost his authority. That was the last time I interacted with him.” Tobin has been incarcerated since then.

Does McAvoy harbor any bitterness or blame towards his stepfather? “No,” he responds firmly. “I know it might sound strange… but I felt loved. I genuinely did. I wasn’t mistreated. No one ever coerced me into actions against my will. Were they supportive? I doubt it was overtly intentional in the beginning, but I believe they didn’t fully understand the impact of their actions. It seems rather negligent,” he explains. “I consistently made informed choices about my actions, and no one ever compelled me.”

Regarding regrets about his past, he states: “I always regret my actions, understanding that they impacted others, but I don’t regret the decade I spent in prison because I learned an immense amount about myself. Yes, I would endure that journey again if necessary.”

For additional information, visit the Alpine Run Project or follow on Instagram