When Edward Enninful was discovered on the underground while traveling through London in 1988, it transformed his existence. The Ghanaian youth, freshly arrived in Britain, was captivated by the capital’s creative landscape of the 90s – starting as a model, transitioning to stylist, and by 18, becoming the fashion director of i-D magazine.

“It was during the peak of the YBA [Young British Artists] scene – Jay Jopling, Tracey Emin. I encountered Kate [Moss] at a casting call,” he reminisces. “Then Naomi [Campbell] for a cover shoot, and I sensed we would become close friends. We all mingled across different disciplines. Fridays extended into Saturdays and Sundays. I long for that raw essence.”

If Enninful appears reflective, he isn’t alone in that sentiment. Recently, the nostalgic glorification of the 90s has reached an enthusiastic high. However, over the years, Enninful perceives a change. “I think we’re less accepting now compared to the 90s,” he states. “It’s not limited to this country – it’s a global issue.”

The regression is hard to overlook: the ascendancy of the far-right, a backlash against “wokeness”, and the resurgence of Eurocentric beauty ideals. In contrast to Tony Blair’s optimism, today, Nigel Farage looms as a possible prime minister. Even the union jack, once a symbol of Cool Britannia, has become controversial once more.

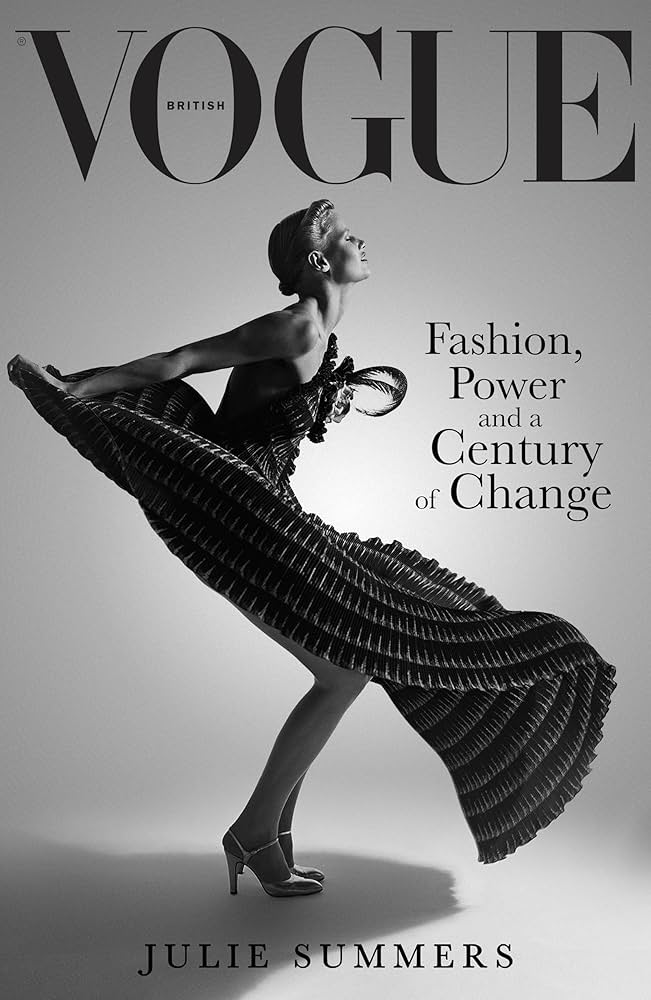

For Enninful, the response has always been a celebration of culture in its entirety. This was the core tenet of his debut issue as editor of British Vogue, back in 2017, depicting a portrait of modern Britain that included Sadiq Khan, Skepta, Steve McQueen, and Zadie Smith among others.

“People who have a platform should utilize it,” he expresses, referring to those editorial decisions. “Everyone discusses immigration; I wouldn’t be here if the UK hadn’t been a welcoming place, if it hadn’t provided my family a home and education. That’s the Britain I’ve always cherished. I hope this phase will pass.”

He finds solace in the new generation: “They’re far more conscious than we were. They discuss implicit bias – I hadn’t even heard of that.”

Enninful feels comfortable discussing the city he adores when we convene at Kensington Roof Gardens as twilight descends over London. Dressed in his typical monochrome attire, Enninful recalls partying here in the 90s, mentioning that there were once flamingos in the garden.

Those formative experiences would forge a career characterized by boldness and inclusivity. Enninful was the first male, black, gay, and disabled gay man of color to lead British Vogue. His covers showcased models of diverse ethnicities, plus-sized women, an octogenarian, a hijab-wearing model, a woman with Down’s syndrome, and essential workers. And sales soared. “Ignoring vast segments of the population doesn’t just reflect a lack of inclusivity – it’s detrimental to business,” he shares.

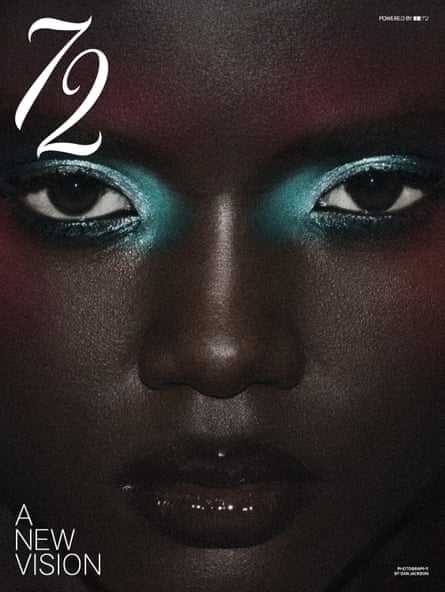

He recently launched his creative firm EE72 and its publication, 72, marking his first significant venture since departing Condé Nast, expressing his desire to continue being a “disruptor”. What does that signify to him?

“I’ve consistently challenged the established norms. I was born and raised in an environment where everyone was black – the doctors, the lawyers, the president. Then we migrated to England, broke, and I became a minority. I was quite introverted. My teachers said I’d never achieve anything. My brothers and I were stopped by the police under the Sus laws … all of that instilled in me a dual nature, a sense of being both within and outside the circle.”

Contrary to the typical image of fashion editors as loud and high-strung, Enninful is softly spoken and radiates tranquility. He has not escaped adversity, openly discussing his experiences with depression and the 14 years he devoted to an Alcoholics Anonymous program.

He has undergone six eye surgeries, including for a detached retina, and now has partial vision. “I spent two years in a dark place, not working, fearful of losing my sight,” he explains. “It’s akin to PTSD; you exist in constant fear. I thought, God, if this ever subsides, I’m going to pursue all the things I was too afraid to attempt. I refuse to limit myself to being just an editor or a fashion figure.”

It is this defiance against being pigeonholed that has propelled Enninful beyond the sphere that established his reputation. He is curating Tate Britain’s groundbreaking 90s exhibition, showcasing works by Juergen Teller, Nick Knight, David Sims, Corinne Day, Damien Hirst, Gillian Wearing, Yinka Shonibare, and others. The exhibition, he explains, aims to capture the era’s creative cross-pollination – and highlight those who weren’t afforded sufficient recognition back then. “Institutions didn’t always acknowledge the right artists because they lacked the necessary pedigree.”

Enninful’s debut as a curator was at the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit at the Thaddaus Ropac gallery in Paris. He also conducted a series of 90s-focused discussions with artists at Art Basel. The second issue of 72, released this week, centers on this year’s Turner prize nominees. He refers to it as “a brand new chapter for me, a significant transition.”

His long-standing friendship with the Tate director, Maria Balshaw, was instrumental in bringing the 90s exhibition to fruition. “We were both from working-class backgrounds who found ourselves in major institutions. We frequently met to exchange thoughts.” After departing Vogue, he proposed the idea of collaborating. “She replied, ‘I have a project for you.’ I instantly agreed.”

One of the most notable characteristics of 72 magazine is its absence of conventional advertising. Instead, the company operates on a model based on collaboration. At one launch event, guests utilized Google’s technology to virtually try on a Moncler capsule designed by Enninful. “We pose the question, what can we create together? Is it an event, a podcast? The magazine is part of a broader ecosystem.”

Could this model be applied to financially struggling museums and galleries? “Absolutely,” he asserts passionately. “We must think creatively. We require these institutions. Upon my arrival in the UK, visiting the National Portrait Gallery changed my life.”

Enninful recently participated in the organizing committee for the British Museum’s inaugural ball, its equivalent of the Met Gala, which raised £2.5m. “Nicholas [Cullinan, the British Museum director] reached out, saying ‘I want to do something that benefits not only the museum but also the nation’.”

Currently, Enninful stands as one of the most impactful creative powerhouses globally. For the launch of 72, he enlisted friends such as Julia Roberts, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Oprah Winfrey. His firm employs 25 individuals across London and New York, with plans to expand into podcasts and films. He enjoys the autonomy of being his own boss – and despite earlier reports of a power struggle, insists that he and Anna Wintour are “on good terms.”

He regards his journey as evidence of the strength found in following one’s passions. After leaving Goldsmiths, University of London, to pursue modeling, he didn’t speak to his father – a prior military officer in Ghana – for 15 years. They later reconciled, and when Enninful received his OBE, his father danced with Madonna at the afterparty and took home his son’s medal. His late mother, a seamstress, nurtured his passion for fashion and encouraged him to always question “why?”.

What might the Edward of the 90s think of the Edward of today? He laughs heartily. “He would be astonished, yet proud. Back then, I was anti-establishment. I didn’t perceive institutions like Tate as belonging to me.”

He considers for a moment. “I never take anything lightly. We lost our home, we escaped our homeland. I nearly lost my sight. Therefore, fear isn’t an option. People have underestimated me throughout my entire career. But once I’ve decided to pursue something, nothing can impede me.”