In 2024, a Democratic congressional hopeful in Pennsylvania, Shamaine Daniels, employed an AI chatbot named Ashley to engage with voters and converse with them. “Hi. I’m Ashley, an AI volunteer supporting Shamaine Daniels’s congressional campaign,” the calls initiated. Daniels did not ultimately succeed. However, these calls might have aided her efforts: Recent studies indicate that AI chatbots can alter voter perspectives in just one conversation—and their effectiveness is quite impressive.

A collaborative team of researchers from multiple universities discovered that interacting with a politically biased AI model proved to be more effective than political ads in swaying both Democrats and Republicans to favor candidates from opposing parties. The chatbots influenced opinions by presenting facts and evidence, although they were not always accurate—in fact, the research indicated that the most convincing models made the most false claims.

The results, outlined in two studies published in the journals Nature and Science, contribute to a growing body of research showcasing the persuasive capabilities of large language models (LLMs). They pose significant questions about how generative AI could transform elections.

“One interaction with an LLM can significantly influence important choices during elections,” states Gordon Pennycook, a psychologist at Cornell University who contributed to the Nature study. LLMs can convince individuals more efficiently than political ads as they provide much more information in real-time and strategically utilize it in discussions, he explains.

For the Nature paper, researchers enlisted over 2,300 participants to talk with a chatbot two months ahead of the 2024 US presidential elections. The chatbot, designed to support one of the leading candidates, was surprisingly convincing, particularly when engaging on candidates’ policies regarding matters like the economy and healthcare. Supporters of Donald Trump who interacted with an AI model favoring Kamala Harris became somewhat more inclined to back Harris, moving 3.9 points toward her on a 100-point scale. This effect was roughly four times greater than the impact of political advertisements seen during the 2016 and 2020 elections. The AI model backing Trump shifted Harris supporters 2.3 points toward Trump.

Similar tests during the preparation for the 2025 Canadian federal elections and the 2025 Polish presidential elections yielded even greater outcomes. The chatbots adjusted opposition voters’ views by roughly 10 points.

Traditional theories about politically motivated reasoning suggest that partisan voters resist facts and evidence that challenge their convictions. However, the researchers found that the chatbots, utilizing a variety of models including versions of GPT and DeepSeek, were more persuasive when they were directed to employ facts and evidence compared to when they were instructed not to. “Individuals are adjusting based on the facts and information that the model provides,” says Thomas Costello, a psychologist at American University involved in the project.

The drawback is that some of the “evidence” and “facts” presented by the chatbots were incorrect. In all three nations, chatbots supporting right-leaning candidates made a higher number of false claims than those advocating for left-leaning candidates. The models are trained on extensive human-written text, which results in the reproduction of real-world patterns—including “political communication from the right, which tends to be less accurate,” per studies on partisan social media content, according to Costello.

In another study released this week, in Science, a partially overlapping group of researchers explored what renders these chatbots so convincing. They tested 19 LLMs with nearly 77,000 participants from the UK on over 700 political topics while altering factors such as computational capacity, training methods, and persuasive strategies.

The most successful technique to enhance the models’ persuasive abilities was to instruct them to support their arguments with facts and evidence and to undergo further training through persuasive conversation examples. In fact, the most convincing model shifted participants who initially disagreed with a political statement 26.1 points toward agreement. “These are substantial treatment effects,” comments Kobi Hackenburg, a research scientist at the UK AI Security Institute involved in the project.

However, optimizing for persuasiveness had a negative impact on truthfulness. As the models became increasingly convincing, they also delivered more misleading or incorrect information—and the underlying reasons remain unclear. “It might be that as the models learn to present more facts, they tap into the less reliable information they possess, leading to poorer quality facts,” states Hackenburg.

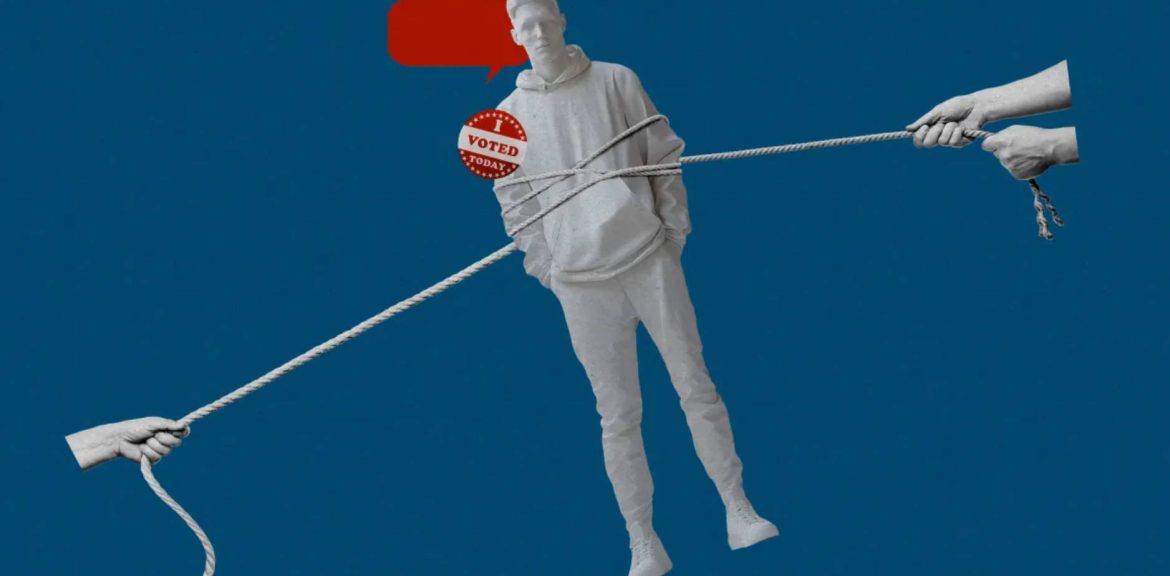

The persuasive influence of chatbots may have significant implications for the future of democracy, the authors caution. Political campaigns utilizing AI chatbots could shape public sentiment in ways that undermine voters’ capacity to make independent political decisions.

Nevertheless, the precise nature of the consequences remains uncertain. “We’re unsure what future campaigns will look like and how they will integrate these technologies,” queries Andy Guess, a political scientist at Princeton University. Competing for voters’ attention is costly and challenging, and engaging them in lengthy political discussions with chatbots may prove difficult. “Will this serve as the primary means for people to educate themselves about politics, or will it remain more of a niche endeavor?” he wonders.

Even if chatbots do become more prevalent in elections, the impact on enhancing truth versus misinformation is unclear. Often, misinformation has an advantage in political campaigns, so the rise of election-focused AIs “could indicate we’re steering toward a crisis,” states Alex Coppock, a political scientist at Northwestern University. “However, it’s also possible that this means correct information will also become scalable.”

This leads to the question of who will have the advantage. “If everyone has their own chatbots operating freely, does that mean we’ll simply persuade ourselves to a standstill?” Coppock questions. Yet, there are reasons to be skeptical about a deadlock. Access to the most persuasive models may not be equally available to all politicians. Additionally, voters across the political spectrum may engage with chatbots at varying levels. “If supporters of a certain candidate or party are more adept with technology than others,” the persuasive effects may not even out, states Guess.

As individuals increasingly rely on AI to navigate their daily lives, they may also begin seeking voting advice from chatbots, regardless of whether campaigns encourage such interactions. This could pose a troubling scenario for democracy unless robust safeguards are implemented to regulate the systems. Assessing and documenting the accuracy of LLM outputs in political discussions could be an initial step.