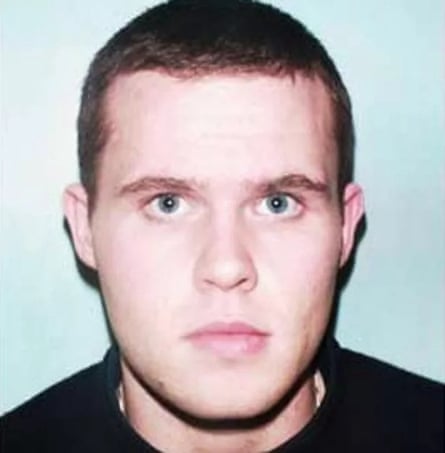

John McAvoy found himself in a holding cell within Belmarsh prison, anticipating processing while scheming his escape. It was 2007, he was 24 years old, arrested for gun-related crimes and conspiracy to carry out a robbery. Facing a lengthy sentence, having previously spent three years incarcerated for firearm possession, he realized his only escape route lay through the hospital wing. Thus, he fabricated a concussion story to the guards, waiting for the opportunity to be transferred. However, upon the opening of the holding cell doors, he was unexpectedly handcuffed and escorted to a high-security unit (HSU).

Upon seeing the unit, the reality of his situation struck hard. “I thought to myself: ‘I won’t see sunlight for a long, long time.’”

The Belmarsh HSU operates as a prison within a jail. Accessing it requires a short bus ride through the main facility, past a secure gate and perimeter. An airlock ensures remote door locks are engaged to deter hostage situations. The HSU spur is limited, featuring approximately eight cells, low ceilings, and fluorescent lighting. “We referred to it as the submarine,” McAvoy reminisces. “Natural sunlight is virtually absent. One wing has no windows whatsoever. It’s extremely.

claustrophobic.” While an exercise yard was available, the sky remained obstructed by security wire. McAvoy’s cellmates included notorious radical preacher Abu Hamza and the 21/7 bombers who failed in their attempts.

“This is the final chapter,” a prison official informed him. It indeed could have been. Yet, for McAvoy, it marked a new beginning: an improbable start on his journey to becoming a celebrated endurance athlete. By his release in 2012, nearly a decade later, he had set three world records and seven British records in rowing—all achieved within the prison gym.

McAvoy was born in London during the early 80s, growing up with his mother and five aunts. He never met his biological father, who passed away shortly before his birth. His mother was employed as a florist. They struggled financially, “yet she did everything within her power to ensure her two children lacked for nothing.” Full of energy and occasionally mischievous, McAvoy spent his childhood in proximity to Crystal Palace Park in south-east London, where he’d build makeshift camps with friends and would fish illegally from the lake.

At eight years old, his mother introduced her new partner, Billy Tobin, into their lives. Other than the occasional uncle or cousin, Tobin was the first constant male figure in McAvoy’s upbringing. Tobin was involved in armed robbery—a fact unbeknownst to McAvoy at that time, who found Tobin captivating. He recalls Tobin’s charm and his elegant attire. “Even at a young age, I sensed that his clothing was high-end.” When Tobin departed, he affectionately ruffled McAvoy’s hair and gifted him a £20 note (the first time McAvoy held paper money). Soon after, Tobin became McAvoy’s stepfather. “It was an overwhelmingly impactful moment.” Ambitious and determined as a teenager, McAvoy wanted to own British Telecom, aiming to become a billionaire.

As he matured, McAvoy learned of the criminal affiliations within his family. His uncle Micky McAvoy participated in the gang that executed the Brink’s-Mat heist—one of the largest thefts in British history, where £26m in gold bullion, cash, and diamonds were taken from a Heathrow warehouse. He was 12 when he viewed Fool’s Gold, the 1992 television film based on the robbery, where Sean Bean portrayed his uncle. “It marked a significant moment of my childhood,” he shares, “seeing Sean Bean amidst £26m in gold bars, all glamorized.” It wasn’t long before he found himself entrenched in his stepfather’s criminal enterprises—at 14, Tobin tasked him with guarding duffle bags filled with £250,000 in cash until someone came to claim it. He received £1,000 for that assignment.

At 16, McAvoy departed from school and procured a firearm. This enraged Tobin, as he sought to steer McAvoy away from reckless deeds. He seized the gun and took his stepson under his guidance. “I had hardly any friends my age,” he reveals. “From 15, I was surrounded by men in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.” These men were all affluent criminals. “I gravitated towards them to glean insights into their world.”

Tobin involved McAvoy in tracking cash delivery trucks, identifying targets, and relaying information upward. Although McAvoy was a reserved teen with communication difficulties, Tobin urged him to assert himself. He also instilled an attitude of distrust towards women, advised against conversations in houses that might be under surveillance, and taught him to only rely on those within his inner circle. He cautioned him to demonstrate no vulnerability and to harbor disdain for authority figures. Anyone linked to the system—government, judges, police—was considered adversaries. “There was always this sentiment against authority and a narrative about systemic corruption. Unbeknownst to me, I absorbed all of this.” A strict moral code prevailed amongst them too: “You don’t harm women, children, or the elderly.”

McAvoy recognized that incarceration was a typical occupational risk in his line of work. “You always have that in the back of your mind, even as you convince yourself that you’ll be the exception living out the Hollywood fantasy,” he states. He was under police surveillance—tracking devices were found on his car—leading him to be constantly aware of being monitored, occasionally spotting the same individuals multiple times.

His initial arrest occurred at 18, following police foiling a robbery estimated to yield £250,000. He led officers in a high-speed chase on the motorway, abandoned the vehicle (and his firearm) in south-east London, and changed into shorts (as advised to blend in during a run) before fleeing on foot. After leaping over garden fences, he thought he had escaped. He located a phone box to call a friend, but was quickly surrounded by armed officers and apprehended. McAvoy received a five-year sentence for firearm possession, serving three, including one solitary confinement.

His second arrest took place in 2005, two years post-release. At 22, McAvoy was en route to rob a cash security vehicle when he noticed an unmarked police car approaching. It was a setup; authorities had been surveilling him and his companions for months. As armed officers emerged from three police vehicles, McAvoy fled through the streets of south London.

“I distinctly remember this internal conversation happening, thinking: ‘I refuse to return to prison.’ I was fully prepared to risk everything to escape them.” After mounting a pavement and colliding with a lamp-post, McAvoy abandoned the car and sprinted on foot, determined to elude the overhead helicopter. A closed-off path ensued. The police caught up, aiming their guns at him. “At that instant, I genuinely thought, ‘This is it,’” he reflects.

McAvoy admitted guilt to one count of conspiracy and another of firearm possession with intent to commit robbery. Three days later, he was sent to Belmarsh.

McAvoy was handed a discretionary life sentence. His uncle Micky, who served 16 years for the Brink’s-Mat heist, advised him to stay connected to reality. “I consistently focused on the present,” he asserts. He tuned into the radio and kept up with news stories. “I steered clear of prison politics. I thought to myself: ‘This isn’t my life. I merely want out of here as swiftly as possible and to regain my life.’”

He received one visit from his mother, a process that took several weeks for the governor to approve. She drove to the facility, then took a bus to the HSU, ultimately meeting in a booth behind armored glass. A prison guard accompanied McAvoy with a pen and notepad. They were forbidden from speaking in code, hiding their mouths, and were under the scrutiny of surveillance cameras. Abu Hamza occupied the booth adjacent to him for a legal consultation. McAvoy had 90 minutes with his mother, acutely aware of the distress it caused her. “I decided right there and then to return to my cell and not see her again until the day of my release, nearly eight years later.”

Initially, he was puzzled as to why he shared the unit with terrorists. He voiced this concern to a visitor from the Ministry of Justice, only to be informed that they aimed to prevent any chance of his escape. “You are regarded as worthless,” states McAvoy. “There was never any discourse about rehabilitation or taking steps towards a positive life. It felt like that’s who you are, and that’s what you’ll always be, and that’s your fate.”

McAvoy claims to be consumed by his goals. He read extensively and kept fit by performing what he’d label “cell circuits”—thousands of sit-ups, step-ups, and push-ups. He embraced solitude, never experiencing dull moments. “I had no mental health [issues] in there,” he notes. “I refused to permit my mind to wander too far ahead.”

After two years at Belmarsh, he was relocated to Full Sutton, a maximum-security prison in Yorkshire, before moving to Lowdham Grange, a Category B facility in Nottinghamshire. Initially, McAvoy’s aspiration was straightforward: endure until transferred to a lower-security prison, then escape. “I thought the moment I had a chance in a semi-open prison, I’d be gone. I’d head to Europe and live a criminal lifestyle. That was my perspective.”

However, three years into his sentence, everything shifted. A close friend, Aaron, perished in a vehicular accident in the Netherlands while trying to flee post-ATM robbery with two accomplices. McAvoy saw CCTV footage of the incident in a news segment the next evening.

“That was the most profound low I’ve ever experienced,” he reveals. “It prompted a significant reality check about my existence and my actions.” This created a grim turning point. “I felt disoriented. I was unsure of my direction and aspirations. I felt confined in a physical space and yearned to break free. I wanted my life to deviate from this path.”

McAvoy headed to the prison gym, where he observed another inmate on a rowing machine who had exceeded the usual gym time. Curious, he learned the prisoner was rowing a million meters for children’s charity. McAvoy inquired with the gym officer about participating similarly. That was how his rowing journey commenced.

“I was clueless about technique or the process. But as I used the machine, I felt like I entered a different realm that transported me away from prison. There was total solitude. No one engaged with me. It was a moment for self-reflection, almost meditative in nature. It had a rhythmic flow.” He now believes he had discovered the runner’s high. “It was like the machine became a part of me.”

McAvoy accomplished the first million meters in a month. He sought permission for more sponsored rows, prompted by a suggestion to replicate the distance of rowing across the Atlantic—5,000 km. “I thought it’d be a fulfilling endeavor to achieve.” One evening, nearing the conclusion of his charity effort, he opted to tackle a particularly challenging 10,000-meter row. A prison officer, Darren Davis, took note of his remarkable achievement. “A few days later, he returned with the record-keeping documents for indoor rowing.”

In just over a year, McAvoy shattered three world records for indoor rowing and seven British records. He obliterated the previous marathon record by seven minutes, claimed the title for the longest continuous row (45 hours), and set the record for the furthest distance rowed in 24 hours (263,396 meters).

McAvoy initially resented Davis, viewing him as an extension of the oppressive system, uninterested in rehabilitation. However, Davis’s consistent encouragement of McAvoy’s abilities ultimately won him over. “He recognized my talent and instilled the belief in me that I could achieve something greater in life.” Davis was present during all McAvoy’s record-setting undertakings inside, often sitting alongside him. If McAvoy was engaged in a 24-hour row, Davis would take leave to support and coach him throughout the duration.

“He transformed my prison experience,” McAvoy states. “He wanted to assist me purely out of kindness. There was nothing more to it than the altruistic nature of a person wanting to help another without personal gain.”

Today, Davis stands as one of McAvoy’s closest friends. “I knew the moment my friend died that I would never return to crime, and I can’t foresee where that path might have led,” acknowledges McAvoy. “But I wouldn’t have the life I enjoy now without Darren’s faith in me and the chances he provided for me to utilize my talents.”

McAvoy pursued a personal trainer certification while incarcerated. Once he transferred to Sudbury, a Category D prison, he secured a position as a trainer at a Fitness First gym. He would catch a 7 am bus from the prison six days a week. While training clients, he studied the methods of endurance athletes. Nine months later, in 2012, he received parole and was released from prison. Just shy of eight years had elapsed since his second conviction. His first act post-release was to visit the grave of his friend Aaron.

With a clear goal in mind, McAvoy aimed to transition into a professional athlete. At 30, recognizing time was limited, he began preparing for a triathlon: he joined a rowing club, learned to swim via YouTube, purchased his first bike, and taught himself to ride. He has since emerged as a formidable endurance athlete, competing in numerous ultramarathons, triathlons, and Ironman challenges.

“Experiencing prison and enduring solitude for years has undeniably molded my character as an athlete,” he states. “Having been in a segregation cell… everything else now feels like a privilege—a luxury.”

His standout race was his inaugural Ironman in 2013 in Bolton town center. Previously, he had observed the event while in prison, and after his release only had six weeks to prepare. “That overwhelming sense of accomplishment lingers with me,” he recalls. “I’d say that remains one of my best performances given the limited training time. And Darren was there at the finish line.”

Initially, McAvoy kept his past a secret from those he met through training. But as rumors spiraled within his rowing club—wondering where this remarkable athlete had been—many began researching him online. He chose to document his story on a blog. Concerns over potential backlash haunted him; worried that people would argue he had done harm and didn’t merit his current life, that he shouldn’t be idolized. However, he is careful to avoid romanticizing his past. In 2016, he published his memoir and has received multiple offers to adapt his life story into a film, all of which he has declined.

Evidently, he appears determined to assume the role of mentor he lacked during his formative years following his stepfather’s entrance into his life. “I have no doubt that if another figure—like Richard Branson or an Olympic athlete—had come into my life during that time, my trajectory would have been vastly different.”

McAvoy’s uncle Micky passed away in 2023. The last encounter McAvoy had with his stepfather occurred in Belmarsh’s reception area in 2002 during a transfer. Hearing his voice, he called out, and they managed to convince the authorities to allow them a brief meeting. They opened Tobin’s cell. “I distinctly recall that day in the reception area of Belmarsh. He was shackled to a guard half his age,” he recounts. “It was surreal—comparing my childhood memories of him, to have spent significant years with him, and then witnessing him in such a feeble state within a prison environment. He had lost all of his former strength. That ended up being the last occasion I ever saw him.” Tobin continues to serve his sentence.

Does McAvoy harbor resentment towards his stepfather? “No,” he replies quite firmly. “I realize it may sound strange… but I felt loved. I truly was. I was never mistreated. No one compelled me to do anything against my will. Did they promote certain behaviors? Initially, I don’t think so, but their influence was possibly somewhat careless,” he notes. “I consistently made conscious choices in my decisions without external pressure.”

When asked if he has any regrets regarding his past, he says: “I always regret my actions as they impacted others, but I don’t regret the ten years I spent in prison, because I gained profound insights about myself. And yes, I would willingly undertake that journey again if necessary.”

For further details, please visit Alpine Run Project or Instagram