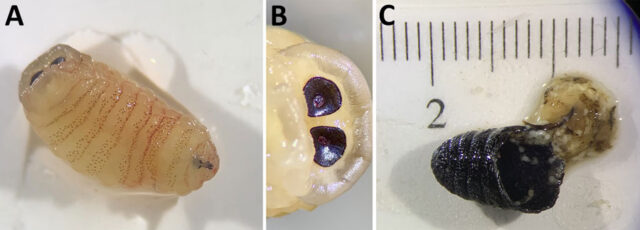

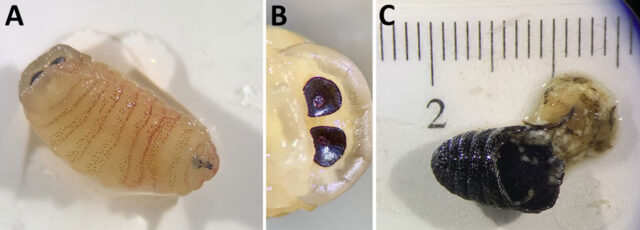

She underwent surgery to extract the mucus-eating pests, which yielded 10 larvae at various developmental stages and one pupa. Genetic testing and DNA sequencing identified them as sheep bot flies, a conclusion supported by visual examination of two third-instar larvae and the puparium.

Credit:

Kioulos, Kokkas, Piperaki, Emerging Infectious Diseases 2026

Nasal novelty

Not only had specialists never encountered a pupa inside a human nose before, they also regarded development to that stage as “biologically implausible.”

“The paranasal sinus environment lacks the temperature and humidity necessary for pupation, and host secretions, immune responses, and resident microbiota produce a hostile milieu for pupal development,” the experts, led by Ilias Kioulos, a medical entomologist at the Agricultural University of Athens, wrote.

Nonetheless, in this patient’s nose the parasites persisted. Kioulos and his colleagues suggest two factors likely promoted the fly’s persistent infestation: a large initial load of larvae and a severely deviated septum.

“From a purely anatomic perspective, we hypothesize that the combination of high larval numbers and septum deviation impeded normal egress from the nasal passages, permitting progression to the [third larval stage] and, in one instance, pupation,” they wrote. Put another way, so many maggots crowded her crooked nasal passage that they created a bottleneck on their way out, allowing some to remain longer than usual. The other, equally troubling possibility is that these flies are adapting to complete their life cycle within human nasal cavities.

The authors note that, in a sense, the woman was lucky. In animals, third-stage larvae trapped in the sinuses generally cannot pupate; they tend to desiccate, liquefy, or calcify, processes that can lead to secondary bacterial infections.

Kioulos and his team warn clinicians to be alert for potential human cases of sheep bot fly infestation, since these flies are widely distributed worldwide.