Since the discovery of nuclear fusion in the 1930s, researchers have been curious about whether we could replicate and harness the process that powers stars—the collision of hydrogen atoms resulting in helium and a remarkable amount of clean energy. By fusing hydrogen, one could generate 200 million times more energy than mere combustion. In contrast to nuclear fission, which fuels the 440 nuclear reactors worldwide, hydrogen fusion emits no dangerous radiation; instead, it produces neutrons that are recaptured and reintegrated into the reaction. Rather than creating long-lived, hazardous waste, fusion generates helium, the most stable element—and a year’s output from a fusion facility wouldn’t be enough to inflate a party balloon business.

Dennis Whyte’s involvement in the fusion endeavor began during his graduate studies, in a laboratory associated with the electric utility Hydro-Québec, located near Montreal. There, he encountered a device designed to replicate stellar fusion on a terrestrial level. It was a doughnut-shaped hollow chamber, sufficiently large for a tall physicist like him to fit inside, based on a design envisioned in 1950 by future Nobel Peace Prize laureate Andrei Sakharov, who also created hydrogen bombs for the Soviet Union. This apparatus was termed a tokamak, a term derived from a Russian expression referring to a “ring-shaped chamber with magnetic coils.”

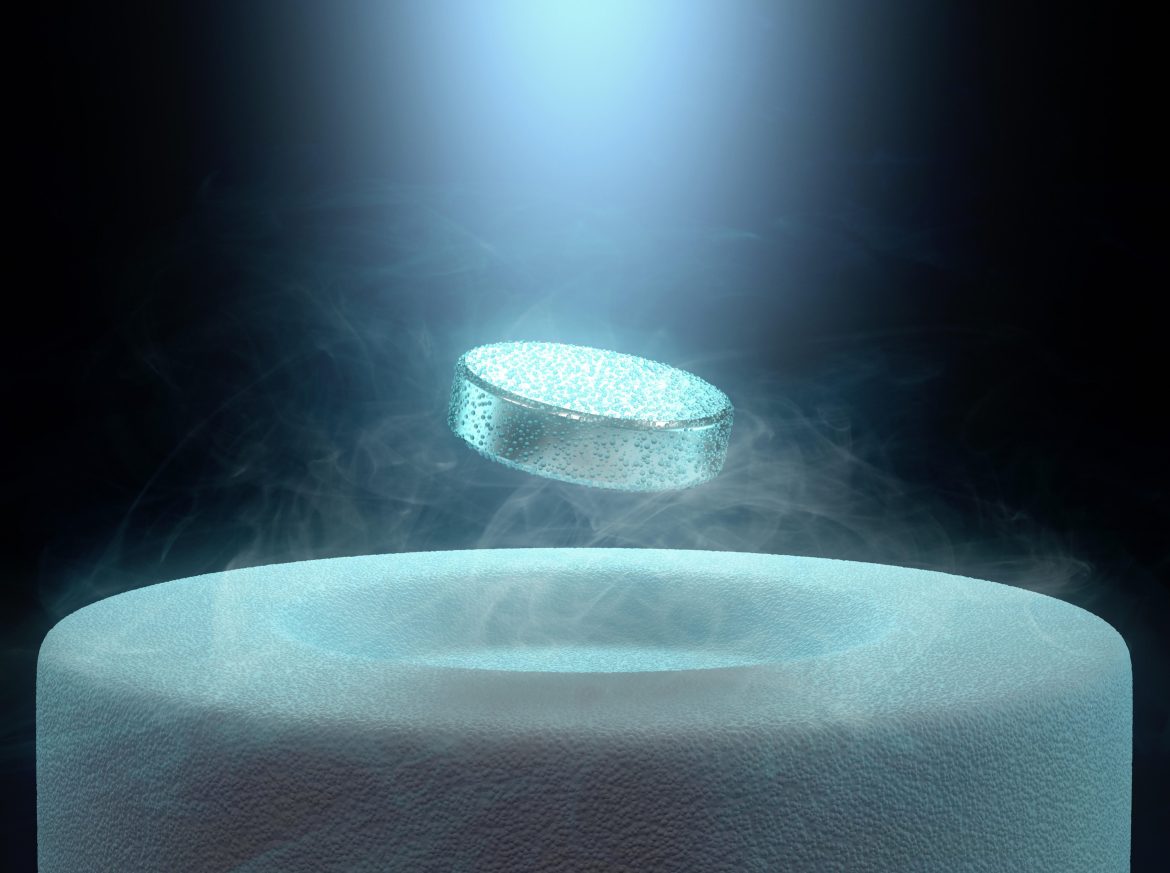

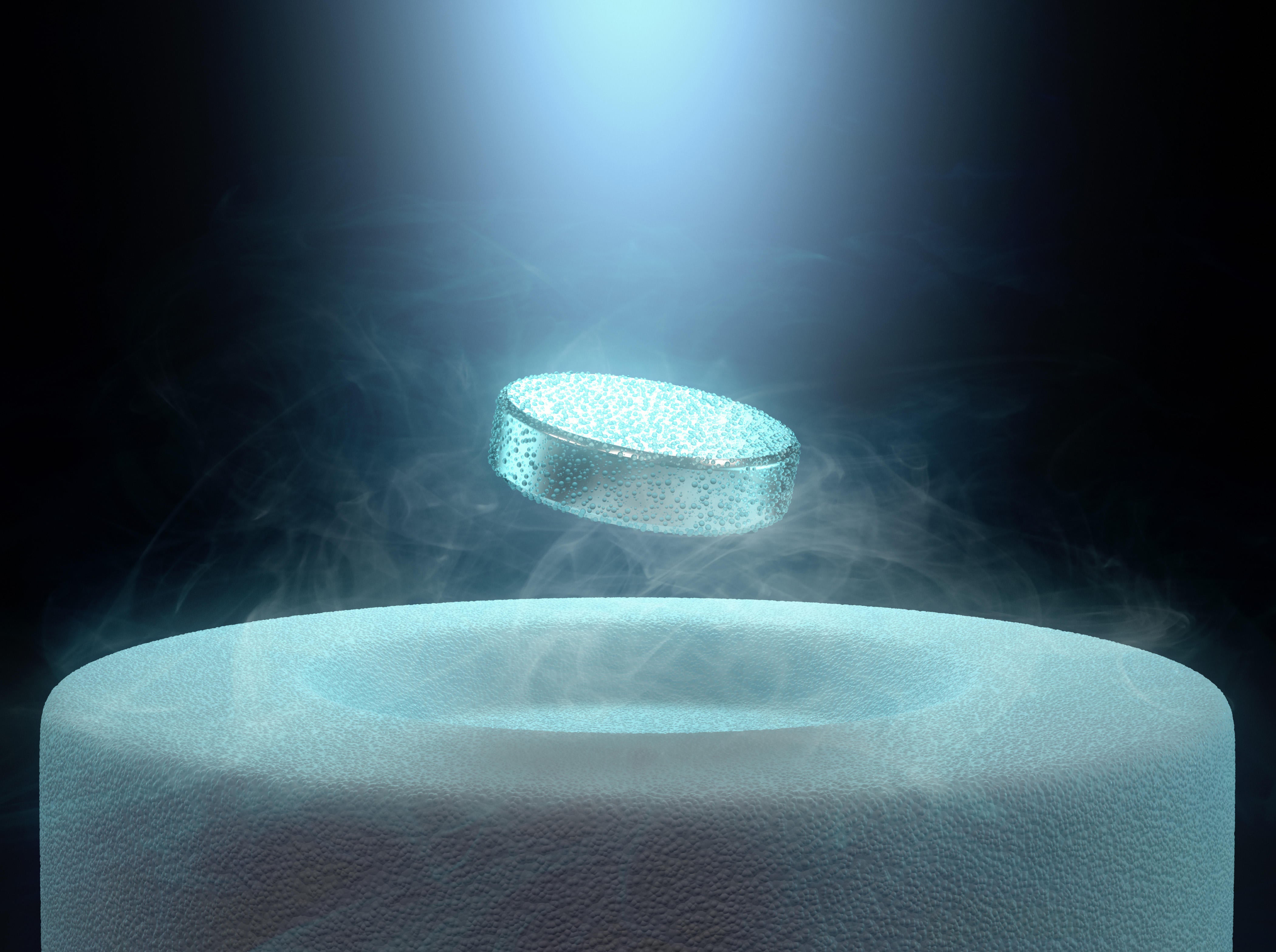

The concept is simple: Fill the doughnut with hydrogen gas and heat it until it transforms into electrically charged plasma. In this ionic state, the plasma is maintained by magnets that encircle the tokamak. Scientists calculated that achieving fusion on Earth without the enormous pressure found in a star’s core would necessitate temperatures nearly 10 times hotter than the sun’s center—approximately 100 million degrees Celsius. Hence, the challenge lay in perfectly suspending the hot plasma in the surrounding magnetic field to prevent it from touching the inner surfaces of the chamber. Such contact would lead to immediate cooling, halting the fusion reaction.

A positive aspect of this was safety. In the event of a malfunction, a fusion power plant wouldn’t experience a meltdown—instead, it would be quite the opposite. The downside was that gaseous plasma could be quite unruly—a minor irregularity in the chamber walls could result in destabilizing turbulence. However, the concept was so enticing that by the mid-1980s, 75 universities and governmental institutions globally had their own tokamaks. If anyone could turn fusion—the most energy-dense reaction in the universe—into a reality, the deuterium from a liter of seawater could meet the electricity needs of one individual for an entire year, providing effectively a boundless resource.

In addition to turbulence, there were two more significant challenges. The magnets encircling the plasma had to be extremely powerful—therefore, quite large. In 1986, 35 nations representing half the world’s population—including the US, China, India, Japan, what is now the entire European Union, South Korea, and Russia—consented to work in unison to create the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, a $40 billion colossal tokamak being built in southern France. Standing 100 feet tall on a sprawling 180-acre site, ITER (the acronym also forms the Latin word for “journey”) is equipped with 18 magnets, each weighing 360 tons, constructed from the best superconductors available at the time. Should it succeed, ITER will generate 500 megawatts of electricity—but not before 2035, if then. Construction is still ongoing. The second, and greatest, challenge is that many tokamaks have briefly attained fusion, but this always required more energy than was generated.

After earning his doctorate in 1992, Whyte contributed to an ITER prototype at the National Fusion Facility in San Diego, taught at the University of Wisconsin, and was employed by MIT in 2006. By that time, he had grasped the immense stakes involved and how groundbreaking commercial-scale fusion energy could be—if it could be sustained and produced cost-effectively.

MIT had been pursuing fusion since 1969. The red brick structures of its Plasma Science and Fusion Center, where Whyte began working, were originally the site of the National Biscuit Company. PSFC’s sixth tokamak, Alcator C-Mod, constructed in 1991, resided in Nabisco’s former Oreo cookie factory. C-Mod’s magnets were wrapped with copper to function as conductors (similar to wrapping copper wire around a nail and connecting it to a battery to create an electromagnet). Before C-Mod was ultimately decommissioned, its magnetic fields, 160,000 times stronger than Earth’s, set the world record for the highest plasma pressure within a tokamak.

However, as delineated by Ohm’s law, metals like copper possess internal resistance, hence it could only operate for about four seconds before overheating—and required more energy to ignite its fusion reactions than it released. Like the now 160 similar tokamaks spread across the world, C-Mod was a fascinating scientific endeavor, yet mainly reinforced the adage that fusion energy was perpetually 20 years away—and always would be.

Each year, Whyte encouraged PhD students in his fusion design courses to create something as compact as C-Mod, one-800th the size of ITER, equipped to achieve and maintain fusion—with an energy gain. But in 2013, as he approached 50, his uncertainties grew. He had dedicated his career to the pursuit of fusion, yet unless significant change occurred, he worried it wouldn’t materialize during his lifetime.

The US Department of Energy opted to scale back its involvement in fusion. It notified MIT that funding for Alcator C-Mod would conclude in 2016. Consequently, Whyte resolved to either abandon fusion and pursue a different path or attempt an alternative approach to expedite the process.

A new generation of ceramic “high-temperature” superconductors had emerged, which were unavailable when ITER’s enormous magnets were being insulated with metallic superconducting cables, needing to be cooled to 4 kelvin above absolute zero (–452.47 °F) for their resistance to current to drop to zero. These new ceramic superconductors were accidentally discovered in 1986 in a Swiss laboratory, and though they had to be cooled to 20 K (–423.7 °F), their power requirements were significantly lower and their output substantially higher, leading to the discoverers being awarded a Nobel Prize the following year.

The potential uses were boundless, but due to the fragility of ceramic materials, coiling them around electromagnets wasn’t practical. One day, Whyte encountered research scientist Leslie Bromberg ’73, PhD ’77, in the hallway, holding what looked like unspooled tape from a VCR cassette. “What’s all that?” he queried.

“Superconducting tape, new stuff.” The lustrous strips were sheathed in ceramic crystals of rare-earth barium copper oxide. “It’s called ReBCO,” Bromberg explained.

Yttrium, the rare-earth component of ReBCO, is 400 times more abundant than silver. Whyte immediately pondered whether superconducting tape could be coiled like copper wire to build much smaller but significantly more powerful magnets.

The class gathered in a windowless room in an ex-Nabisco cracker factory, surrounded by blackboards.

He tasked his 2013 fusion design class with this challenge. If the students succeeded in doubling the strength of a magnetic field enclosing hot plasma, they could potentially amplify fusion’s power density sixteenfold. They conceptualized a groundbreaking design they named Vulcan. It resulted in five peer-reviewed publications—but it remained uncertain whether the layers of wound ReBCO tape could endure the stress of the current needed to maintain plasma suspended while being superheated to initiate a fusion reaction.

For two years, his classes refined the Vulcan concept. By 2015, with the quality and supply of ReBCO improving, he encouraged his students—11 males and one female, including an Argentine, a Russian, and a Korean—to surpass what 35 nations had been striving for nearly three decades.

“Let’s see if ReBCO enables us to construct a 500-megawatt tokamak—comparable to ITER, just much smaller.”

If superconducting tape could facilitate constructing a fusion reactor compact enough to fit into the space of a decommissioned coal-fired plant, he argued, it could seamlessly integrate into existing power grids. To generate enough carbon-free energy to prevent the planet’s climate from being pushed beyond the brink, the components would need to be mass-produced, so any qualified contractor could assemble and service them.

The class convened in a windowless space in a former Nabisco cracker factory, encircled by blackboards. Divided into teams, the students set out to determine how thin-tape electromagnets could be made durable and how to capture neutrons emitted from fusion reactions so their heat could be utilized for powering a turbine—and to foster breeding additional tritium for the plasma. This is essential since natural tritium is exceedingly scarce. The smaller ReBCO-wrapped magnets allowed for reductions in component sizes, creating a ripple effect throughout the entire design. Innovations from one team benefitted another, and elements of the design began to interconnect. As enthusiasm surged through PSFC, participants from prior classes, now postdocs or faculty, joined in. Whyte’s students, some facing doctoral dissertations, were clocking 50-hour weeks on this project, reminding him of the initial reasons he had aspired towards fusion.

Whyte examined it for the thousandth time. He was relatively certain they hadn’t violated any physical laws.

The blanket’s heat would be harnessed for electricity—although one-fifth of the thermal energy would remain within the plasma, meaning that the reaction was now self-heating and self-sustaining, producing more energy than was necessary to initiate it. Net fusion energy was successfully achieved.

The ReBCO magnets, though merely 1/40th the size of ITER’s, could produce a magnetic field strength of 23 tesla (a hospital MRI machine typically operates at 1.5 tesla). This was ample to instigate a fusion reaction, yet it would consume less electricity than its copper-clad C-Mod predecessor by a factor of 2,000. Every component was designed for easy maintenance, allowing for parts to be replaced without needing to disassemble the entire reactor.

The most crucial aspect was that the projected energy output exceeded 13 times the input.

Whyte examined it again for the thousandth time. He was confident they hadn’t breached any physical laws. He calculated the cost per watt and was taken aback. Suddenly, their aim transformed from merely creating a much smaller ITER to achieving commercial viability.

Astounded, he shared with his wife, “This can genuinely be realized.”

Their project was dubbed ARC, which stands for “affordable, robust, compact.” “Buildable in a decade,” Whyte forecasted.The peer-reviewed article published by his 12 students in Fusion Engineering and Design predicted that it would cost around $5 billion. In 2015, that was not substantially more than the expense of a similarly sized coal-fired power plant, and one-eighth of ITER’s price tag.

That May, Whyte delivered a keynote about ARC at a fusion engineering symposium in Austin, Texas. Four of his students were present. When he outlined their vision for a functional reactor by 2025, in just 10 years, attendees were astonished—others were discussing timelines extending into decades. Following the event, the MIT group enjoyed lunch at Stubb’s Bar-B-Q. It was evident that with the climate crisis escalating and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emphasizing the necessity for yet-to-be-invented technologies to prevent temperatures from rising to alarming levels, they had to act. Yet, with the DOE retracting funding, how could they proceed?

On a napkin, Whyte began jotting down what they would need to accomplish and estimated the cost of each step. Over their meal, they crafted a proposal to establish a startup to secure venture capital for financing a SPARC (for “soon-as-possible ARC”) demonstration fusion reactor to prove this could materialize. Then, they would scale up to a commercial version of ARC.

Forming a company would liberate them from the constraints of academic and governmental funding cycles, but they were plasma physicists, most still in their 20s, lacking business backgrounds. Nonetheless, Whyte and Martin Greenwald, deputy director of the PSFC, consented to join them, and in 2018 Commonwealth Fusion Systems, CFS, was born. Three of Whyte’s former students assumed leadership roles in the company, while three remained associated with MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center, which would serve as CFS’s research division in a profit-sharing agreement.

Their office was established up the street in The Engine, MIT’s “tough tech” startup incubator, attracting interest from climate-focused investors like Bill Gates, George Soros, and Jeff Bezos. Yet they were not the sole contenders vying for fusion funding, leading to a competitive race to achieve commercial-scale fusion first.

The CFS team may have been relatively young, but thanks to its partnership with MIT and a coalition of over a hundred seasoned fusion scientists, they had a decisive advantage.

By the end of 2021, Commonwealth Fusion Systems had secured over $2 billion in funding and commenced development on 47 acres outside Boston for a commercial fusion energy site, aiming to complete SPARC by 2025—and a commercially viable, mass-producible ARC by 2030.

Achieving and maintaining net energy is consistently referred to as fusion’s elusive “holy grail,” yet by September 2021, the CFS team, led by CEO Bob Mumgaard, SM ’15, PhD ’15 (a coauthor of the Vulcan design), chief science officer Brandon Sorbom, PhD ’17 (lead author of the 2015 fusion design class’s breakthrough paper), Whyte, and their 200 CFS colleagues were confident they could achieve it—provided their magnets performed adequately. For three years, uninterrupted by the pandemic, they had been engaged in PSFC’s West Cell laboratory, the expansive former Oreo factory that once housed Alcator C-Mod, diligently addressing challenges such as how to solder thin-film ReBCO tape together into a configuration resilient enough to tolerate 40,000 amps flowing through it—sufficient to power a small town.

The completed SPARC would contain 18 magnets surrounding its plasma chamber, but for this initial test, only one had been constructed. It consisted of 16 layers, each a D-shaped, 10-foot-high steel disk grooved like a vinyl record. On one side, the grooves contained tightly wound spirals of ReBCO film, a total length of 270 kilometers—the distance from Boston to Albany. “Yet all that ReBCO comprises just a small amount of rare earth,” remarked Sorbom. “That’s the wonder of superconductors: A minuscule amount of material can conduct substantial current. In contrast, a wind turbine’s rare-earth neodymium magnets weigh tons.”

On the opposite side of each disk, the grooves directed liquid helium to cool the superconductor to eliminate resistance. (The design traces back to the first high-field magnet ever constructed, created at MIT in the 1930s, which utilized copper conductors and water as a coolant.) Each layer was fabricated on an automated assembly line. “The objective,” Mumgaard stated, “is to eventually produce 100,000 magnets per year. This cannot merely be a scientific curiosity. It must become a viable energy source.”

Despite the receding threat of covid-19, an outbreak could disrupt everything, so they adhered to coronavirus protocols, relocating computer terminals outdoors under a tent to minimize crowding inside. Others worked remotely. For a month, myriad team members engaged in eight-hour, continuous shifts. Some operated the electromagnetic coil, encased in stainless steel at the room’s center, which had to be gradually cooled from room temperature of 298 K down to 20 K before slowly increasing to full magnetic intensity. Others consistently monitored real-time data in conjunction with backup models. As the temperature lowered, the internal connections, welds, and valves contracted at varying rates, thus they remained vigilant for any leaks.

On September 2, 2021, the Thursday preceding Labor Day, they began increasing the current by a few kiloamps, pausing frequently to assess what the readings revealed, how the cooling characteristics shifted, and how the stresses on the ReBCO coil escalated as the magnetic field intensified to record levels.

Two nights later, they pushed the current closer to their target: a 20-tesla magnetic field, strong enough to levitate 421 Boeing 747s or contain a continuous fusion reaction. They had set their sights on 7:00 a.m. Sunday, the 5th. At 3:30, the large display in the design center indicated they’d achieved 40 kiloamps, with the magnetic field reaching 19.56 tesla.

By 4:30 a.m., it had increased to 19.98 tesla. An eerie silence fell. At 5:20 a.m., every redundant on-screen meter displayed 20 tesla, and there were no leaks or explosions—except under the tent, where celebratory champagne corks were popping.

Five years prior, during its last four-second operation, C-Mod’s copper-conducting magnet had consumed 200 million watts of energy to achieve 5.7 tesla. This test required just 30 watts—substantially less energy, by a factor of roughly 10 million, Whyte informed journalists—to generate a magnetic field strong enough to support a fusion reaction. The joints responsible for transferring current from one layer to the next performed even better than anticipated. This was the most significant unknown factor, as testing them could only be done in the magnet itself. They appeared to be remarkable.

After five hours, the team reduced the power. “It’s a Kitty Hawk moment,” remarked Mumgaard.

Adapted from Hope Dies Last: Visionary People Across the World, Fighting to Find Us a Future by Alan Weisman, published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Random House. © 2025 by Alan Weisman.