Upon initial observation, it seems like the beginning of a human pregnancy: A spherical embryo gently presses against the welcoming lining of the uterus and then secures itself, burrowing in as the initial strands of a forthcoming placenta become visible.

This event is implantation—the instant that pregnancy officially starts.

Yet none of this is taking place within a body. These visuals were taken in a laboratory in Beijing, within a microfluidic chip, while scientists observed the process unfold.

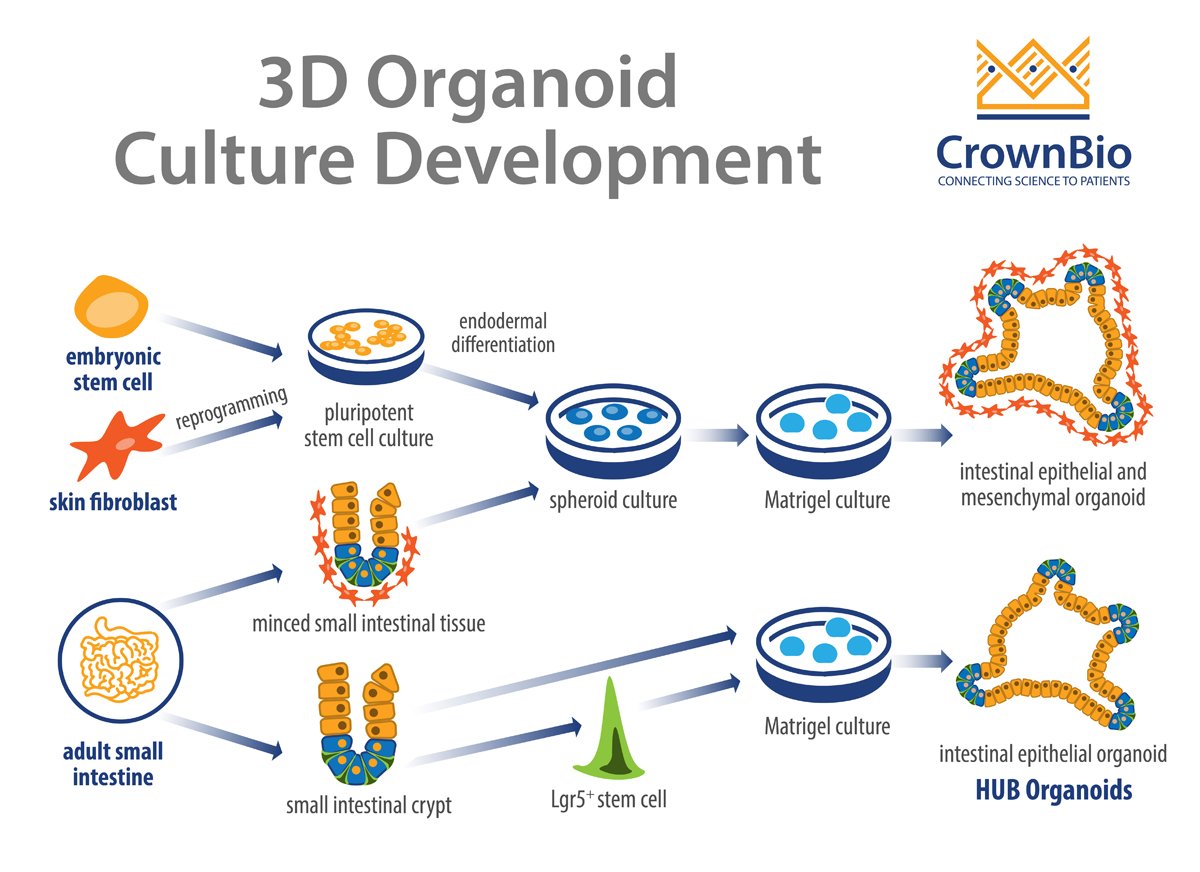

In three studies released this week by Cell Press, scientists are presenting what they describe as the most precise attempts to simulate the initial moments of pregnancy in the laboratory. They have taken human embryos from IVF facilities and permitted these to combine with “organoids” composed of endometrial cells, which create the uterus lining.

The publications—two from China and one involving collaboration among researchers from the United Kingdom, Spain, and the US—demonstrate how scientists are employing engineered tissues to gain deeper insights into early pregnancy and possibly enhance IVF results.

“You possess an embryo and the endometrial organoid together,” states Jun Wu, a biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, who contributed to both Chinese studies. “That’s the main takeaway from all three publications.”

As indicated in the studies, these 3D combinations serve as the most complete replicas of the early days of pregnancy and should be beneficial for exploring why IVF treatments frequently do not succeed.

In every instance, the experiments were concluded when the embryos reached two weeks of age, if not earlier. This is due to legal and ethical regulations that typically prevent scientists from proceeding beyond 14 days.

In a standard IVF operation, an egg undergoes fertilization in the lab and develops into a spherical embryo known as a blastocyst—a process lasting a few days. The blastocyst is then implanted into a patient’s uterus with the hope that it will secure itself there and ultimately develop into a baby.

However, this is a frequent failure point. Many patients discover that their IVF procedure was unsuccessful because an embryo did not attach.

In the recent studies, it is that initial connection between the mother and embryo that is being replicated in the laboratory. “IVF denotes in vitro fertilization, but now this represents the stage of in vitro implantation,” remarks Matteo Molè, a biologist at Stanford University whose findings with collaborators in Europe are included in today’s publications. “Given that implantation is a barrier [to pregnancy], we have the potential to enhance success rates if we can model it in the lab.”

Typically, implantation is completely concealed from view as it occurs within someone’s uterus, according to Hongmei Wang, a developmental biologist at the Beijing Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, who co-led the effort there. Wang often conducts studies on monkeys because she can interrupt their pregnancies to gather the necessary tissues for observation. “We have always aspired to understand human embryo implantation, but we have lacked a method to do so,” she states. “It all occurs within the uterus.”

In the Beijing research, investigators examined approximately 50 donated IVF embryos, but they also conducted a thousand additional experiments using so-called blastoids. The latter are replicas of early-stage human embryos produced from stem cells. Blastoids can be generated in large quantities and, because they are not true embryos, face fewer ethical restrictions regarding their use.

“The inquiry was, if we possess these blastoids, what can we utilize them for?” asks Leqian Yu, the leading author of the report from the Beijing Institute. “The obvious subsequent step was implantation. So how do you achieve that?”

For the Beijing group, the solution was constructing a soft silicone chamber with tiny channels to supply nutrients and a place for the uterine organoid to grow. Afterward, blastoids—or actual embryos—could be introduced through an opening in the device, allowing the “pregnancy” to commence.

“The crucial question we aim to explore is what constitutes the first cross-talk between the embryo and the mother,” states Yu. “I believe this may be the first occasion we can observe the entire process.”

Medical uses

This is not the first instance researchers have attempted using organoids for this type of investigation. At least two startup companies have secured funding to commercialize comparable systems—in certain cases presenting the organoids as a tool to predict IVF success. In addition to Dawn Bio, a startup located in Vienna, there is Simbryo Technologies in Houston, which announced last month that it would begin providing “personalized” predictions for IVF patients utilizing blastoids and endometrial organoids.

To conduct that assessment, doctors will perform a biopsy of a patient’s uterine lining and cultivate organoids from it. Subsequently, blastoids will be added to the organoids to determine if a woman is capable of supporting a pregnancy or not. If the blastoids fail to begin implantation, it could imply that the patient’s uterus is not receptive and that is the reason IVF isn’t succeeding.

The Beijing team believes that the pregnancy organoids could also be utilized to identify medications that may assist those patients. In their paper, they detail how they created organoids from tissue taken from women who have experienced repeated IVF failures. They then examined 1,119 approved drugs on those samples to ascertain if any exhibited improvements.

Several appeared to have beneficial effects. One compound, avobenzone, an ingredient in certain types of sunscreen, raised the likelihood that a blastoid would begin to implant from merely 5% to approximately 25%. Yu mentions that his center aims to eventually initiate a clinical trial if they can discover the right medication to test.

Artificial womb?

The Beijing group is exploring methods to enhance the organoid system to make it even more realistic. Currently, it lacks critical cell types, such as immune cells and a blood supply. Yu states that a next step he is working on involves incorporating blood vessels and miniature pumps into his chip device, allowing him to provide the organoids with a rudimentary form of circulation.

This implies that in the near future, blastoids or embryos could potentially be cultivated for longer durations, provoking questions about how far researchers will be able to extend pregnancy within the laboratory. “I believe this technology does raise the possibility of extending growth periods,” remarks Wu, who notes that some regard the research as a preliminary step toward creating infants entirely outside the body.

Nonetheless, Wu emphasizes that incubating a human to term in a laboratory remains unattainable for now. “This technology is certainly connected to ectogenesis, or development outside the body,” he states. “However, I don’t believe it is anywhere close to an artificial womb. That remains within the realm of science fiction.”