As many individuals gear up for shopping, baking, and preparations for the holiday period, nuclear power facilities are also preparing for one of their most active times of the year.

In the US, nuclear reactors exhibit consistent seasonal patterns. The highest demand for electricity typically occurs in summer and winter, prompting plant operators to schedule maintenance and refueling during other times of the year.

This regular scheduling might appear routine, but it’s remarkable that operational reactors maintain such reliability and predictability. It sets a high standard for upcoming technologies aspiring to join the existing fleet in the near future.

In general, nuclear reactors function at steady levels, aiming for maximum capacity. In 2024, the global average capacity factor for commercial reactors—the ratio of actual energy output to the theoretical maximum—was 83%, while North America recorded an average of around 90%.

(It’s worth mentioning that using this figure alone may not accurately represent comparisons among various types of power plants—natural gas facilities may demonstrate lower capacity factors, primarily because they are often deliberately turned on and off to accommodate fluctuating demand.)

Those impressive capacity factors may underestimate the true reliability of the fleet—much of the downtime is planned. Reactors require refueling every 18 to 24 months, with operators typically scheduling these outages for spring and fall, when electricity consumption is lower compared to the peak summer or winter periods.

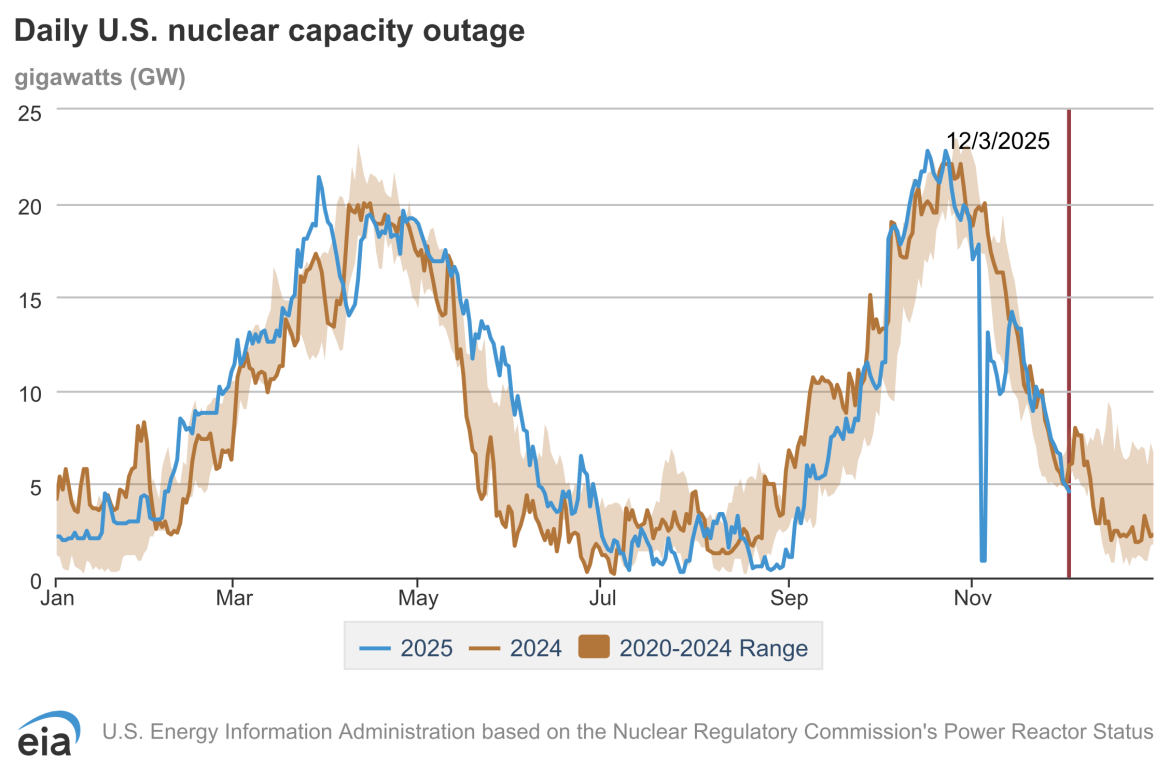

Review this chart of nuclear outages from the US Energy Information Administration. There are certain days, particularly during peak summer, when outages are minimal and nearly all commercial reactors in the US are operating at close to full capacity. On July 28 this year, the fleet recorded an operation level of 99.6%. In contrast, on October 18, the capacity was down to 77.6% as reactors underwent refueling and maintenance. Now, as we approach another busy period, reactors are starting to return online, and shutdowns are at a low again.

However, not all outages are pre-planned. At the Sequoyah nuclear power station in Tennessee, a generator failure in July 2024 brought one of the two reactors offline, resulting in nearly a year-long outage. (The utility also took the opportunity for maintenance during this period to extend the lifespan of the plant.) Just days after that reactor was reactivated, the entire facility had to shut down due to low water levels.

And who can overlook the earlier incident this year when jellyfish disrupted operations at not just one but two nuclear power stations in France? In the second event, these creatures infiltrated the filters of machinery that extracts water from the English Channel for cooling purposes at the Paluel nuclear facility. This led to a significant cut in output, although it was restored within days.

Excluding jellyfish incidents and occasional maintenance, the global nuclear fleet functions with considerable reliability. This was not always the case. Back in the 1970s, reactors operated with an average capacity factor of merely 60%. They were often offline just as frequently as they were operational.

The current fleet of reactors has greatly benefited from years of experience. We now observe a growing number of companies focused on introducing new technologies to the nuclear sector.

Next-generation reactors utilizing novel materials for fuel or cooling are poised to learn valuable lessons from the existing fleet, but they will also confront unique challenges.

This could imply that initial demonstration reactors may not match the reliability of the current commercial fleet immediately. “First-of-a-kind nuclear, similar to other pioneering technologies, is quite complex,” asserts Koroush Shirvan, a professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT.

This indicates that it may take time for molten-salt reactors or small modular reactors, or any of the other designs to navigate technical challenges and establish their own operational rhythm. It has taken decades to reach a point where we expect the nuclear fleet to adhere to a well-defined seasonal pattern based on electricity demand.

There will always be hurricanes, electrical failures, and jellyfish invasions that create unforeseen issues and compel nuclear plants (or any power facilities, for that matter) to cease operations. However, in general, the current fleet maintains an exceptionally high level of consistency. One of the significant challenges ahead for next-generation technologies will be demonstrating that they too can achieve similar performance.