The calendars of the Maya were managed by experts referred to as “daykeepers,” a cultural practice that persists to this day. There is broad agreement that eclipses held significance for the Maya. “They were monitoring them, they had ceremonies associated with [eclipses], and it was integrated into their belief system,” Lowry informed Ars. “Thus, we recognize that the eclipse table is part of the cultural understanding of that era. Our objective was to determine how the table reached its present form.”

A forecasting system

The examination conducted by Lowry and Justeson included mathematical modeling of the eclipse forecasts found in the Dresden Codex table and contrasting the findings with a historical NASA database. They concentrated on 145 solar eclipses that would have been observable in the Maya region from 350 to 1150 CE.

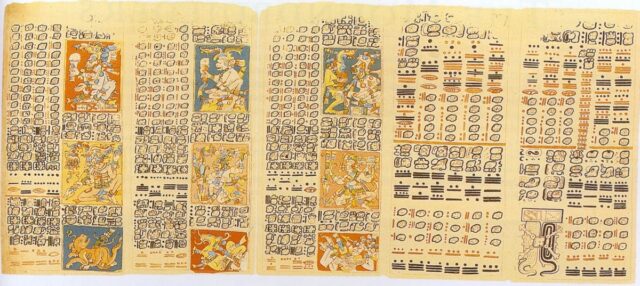

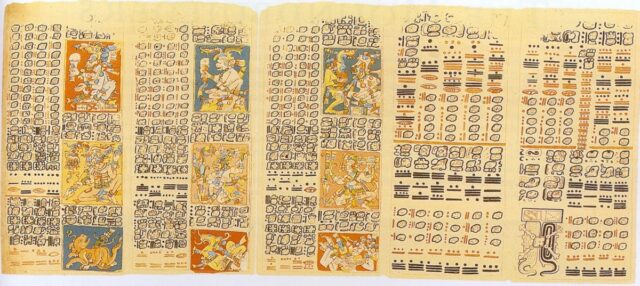

Initial publication in 1810 by Alexander von Humboldt, who redid five pages for his atlas.

Credit:

Public domain

The researchers concluded that the eclipse tables in the codex developed from a more general series of consecutive lunar months. The duration of a 405-month lunar cycle (11,960 days) correlated with a 260-day calendar (46 x 260 =11,960) much more closely than with solar or lunar eclipse cycles. This indicates that the daykeepers determined that nearly 405 new moons corresponded with 46 cycles of the 260-day calendar, a realization the Maya utilized to successfully forecast the dates of full and new moons across 405 consecutive lunar dates.

The daykeepers also comprehended that solar eclipses appeared to happen on or around the same day in their 260-day calendar and, gradually, learned how to foresee the days when a solar eclipse might take place locally. “An eclipse occurs only during a new moon,” Lowry remarked. “The necessity for it to be a new moon implies that if you can predict a new moon accurately, you can forecast a one-in-seven chance of an eclipse. This is why it is logical that the Maya are refining lunar prediction models for accurate eclipses, since they do not need to ascertain the moon’s position concerning the ecliptic.”

The Maya further recognized that they needed to periodically adjust their tables to accommodate temporal discrepancies. “When we discuss accuracy, we sometimes consider the ability to predict something down to the microsecond,” Lowry noted, referencing NASA data. “The Maya possess a very precise calendar, but they predict to the day, rather than to the second.”