It took Joe Meanen approximately six seconds to reach the North Sea, following a jump of 175ft (53 metres) from the ablaze ruins of the Piper Alpha oil platform. The descent felt like an eternity, during which he recalls thinking: “What on earth have I done?”

Piper Alpha was located roughly 120 miles off Aberdeen, on Scotland’s northeast coast. On July 6, 1988, it experienced multiple devastating explosions and fell apart, resulting in the deaths of 167 out of the 228 crew members, along with two from the rescue team.

It was a Wednesday, and Meanen anticipated just one more day of his two-week assignment on the platform before heading home on Friday morning. He shared accommodations with three others, all of whom were uplifted knowing they would soon have time off with loved ones on solid ground. One of them, David Campbell, had just received news of his upcoming fatherhood.

Around 9pm that night, Meanen and his roommates took some Mars bars and joined about 40 other crew members in the cinema. Significant construction and upgrades were being carried out on Piper Alpha at the time, yet due to the volume of oil produced, the platform continued operating. Meanen recalled feeling apprehensive regarding the implications of the ongoing work: “You could smell gas throughout the platform. At times, I even believed I could smell it inside the accommodations.”

At 10pm, a non-functional gas pump, which lacked a safety valve due to ongoing upgrades, was mistakenly activated and erupted, triggering the initial explosion. “The whole platform swayed back and forth,” Meanen recounts. “Part of the cinema roof caved in, plunging everything into complete darkness – the lights went out – causing chaos in the cinema with people shouting to get outside.”

Upon exiting the cinema, Meanen tried to apply the safety training he had undergone for offshore work. However, as he aimed for his designated lifeboat, he realized the seriousness of the explosion. “The main control room was utterly obliterated in the first blast. Consequently, no Tannoy [announcements] were made. No alarms sounded. People were essentially lost.”

“My immediate thought was to access my lifeboat master station. But as I made my way to the west side of the platform, others were returning, warning [there was] no way to escape that route because the smoke was too dense.” The blaze was fueled by oil, he explains, “which generates thick, black, acrid smoke, meaning anyone stepping outside without breathing apparatus would last a mere two or three minutes at most before succumbing to smoke inhalation.”

In the chaos, Meanen lost sight of his accommodations mates. He would never see two of them again, including Campbell – the soon-to-be father.

Meanen carefully considered his next actions. “Most individuals had gone to the galley area, marked as a safe zone. It was fireproofed and had positive airflow [a sort of ventilation system to shield it from fumes], which should have deterred smoke from entering.”

However, as he huddled there with around 100 men, using a damp dish towel to shield his face from smoke inhalation, it became evident that he had to keep moving. “You could hear other minor explosions taking place,” he notes. “You could sense these groaning and creaking sounds. It was the platform’s framework, which had been compromised and was beginning to melt, starting to fall apart – we didn’t recognize that back then. It was twisting and buckling, and windows were shattering, letting more smoke in.”

Meanen and a few others resolved to make their way to the helideck to ensure they would be seen quickly if any helicopters came for rescue, while six men opted to remain in the galley. Meanen was among the last to depart that area, shouting back: “‘Are you not coming with us?’ They looked at each other and replied: ‘No, we’ve been instructed to stay, so we’re just going to stay.’ I said: ‘Alright, good luck.’”

The remains of the six men who stayed in the galley were recovered three months later, as he recounts. The galley had plummeted 475ft (145 metres) to the seabed after Piper Alpha’s entire structure collapsed.

As Meanen and other crew members ascended to the helideck through the dense black smoke, they were hit with the grim reality of the situation. “It was the first proper time we had been outside since the initial explosion,” he states. “And it became immediately clear that there was no possibility of any helicopters getting even close to the platform, let alone attempting to land on it.”

From that height, they were able to see nearby oil platforms, including the firefighting rig Tharos, which happened to be adjacent to Piper Alpha that night and began spraying water onto the flames. “There were 14 of us and we were waving at the Tharos. I’m sure they noticed us.”

Then came the second significant explosion, this time caused by a gas pipeline from a neighboring oil platform, the Tartan, which ruptured from the intense heat radiating from Piper Alpha. “We didn’t actually understand what had occurred,” Meanen explains, “but we realized it was something dreadful. Everyone just clamored on top of one another. As people stood up, they bolted in various directions, not another word exchanged.”

This was the moment Meanen recognized that his lone chance of survival was to leap from the platform into the North Sea, hoping to be rescued by the teams below.

Acting swiftly, he hurled a lifejacket over the edge of the helideck and jumped, launching himself as far as possible. He mentions that his recollection of the escape is murky, but during his fall, he suffered burns to his arms as they whipped through the air. He didn’t make contact with the fireball during the descent, but the heat was so extreme that being in proximity alone was enough to cause scars.

After what seemed like an eternity, he splashed into the water. By following the illumination from the flames engulfing Piper Alpha, he swam to the surface, where he discovered his lifejacket bobbing in the sea and managed to exploit this along with the roof of a lifeboat that had been propelled from the rig to keep himself afloat.

He noticed the hull of the lifeboat and headed straight for it. After climbing aboard and drifting away from Piper Alpha, he could finally gaze upon the remnants of the platform from which he had narrowly evaded disaster. “I was looking back at the platform … trying to imprint the image into my head and thinking: if there’s anyone else left on that platform, they’re lost. But in actuality, there were people who escaped after I did.” From the group of 14 who made it to the helideck, Meanen was among the five survivors.

A rescue vessel located him and transported him to a larger supply ship for medical assistance at a nearby oil rig. He was subsequently flown by helicopter to Aberdeen, where he was taken directly to the hospital for treatment. He never returned to offshore work.

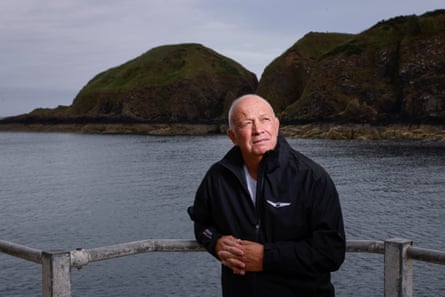

Meanen commenced his rig career at 22, during the apex of the 80s North Sea oil boom. By the time of the tragedy, he was 29 and working at Piper Alpha as a scaffolder. Originally from Glasgow, he relocated to the northeastern coastal town of Stonehaven upon commencing work on oil platforms.

Piper Alpha was operated by Occidental Petroleum (Caledonia) Ltd (OPCAL) and functioned as the center of a network of pipelines linking it to adjacent platforms and the shore. In 1988, the platform was responsible for about 10% of North Sea oil and gas output and was the largest single oil and gas producer globally. At its zenith, it yielded around 300,000 barrels of oil daily.

In the months following the Piper Alpha incident, Meanen found himself frequently hospitalized as he recovered from his burns, sharing his account and taking photographs of his injuries for the investigation into the disaster. He also contemplated his future. The Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster commenced in November 1988 and lasted 13 months to conclude. The resulting report criticized Opcal and held the company accountable for insufficient maintenance and safety protocols. However, no criminal charges were filed against the company. The report also proposed 106 recommendations for altering North Sea safety standards. Occidental disbursed $180m in compensation to survivors and the families of the deceased.

It wasn’t until Christmas that year, while Meanen sat in his living room, that the sorrow overwhelmed him. “I was planning to go to my mum’s later for Christmas dinner,” he recalls. “I just woke up in the morning and turned on the TV, as most do, and suddenly I was overtaken by grief.

“It was the first instance it had truly hit me, and all I could contemplate was that this would be the first Christmas for the mums and dads, the siblings, the wives and partners, and all the kids – this would be the first time they’d be without their dads or their brothers or their uncles, or their sons.”

Despite an initial struggle to confront his grief, Meanen has come to embrace the notion that he should openly discuss his experiences on Piper Alpha. “I believe: nothing wrong with expressing a bit of emotion and articulating how you feel … I’ve always been open to sharing and bringing it to light. I tend to focus more on the positive aspects; how fortunate I was.”

In the early 90s, Meanen along with a few other survivors initiated a tradition of annual meet-ups in Edinburgh (the city they initially had to visit for their personal injury claims). “It’s wonderful,” he states. “Sometimes Piper Alpha doesn’t even come up in our talks; it’s just fantastic to reconnect. If the subject happens to arise, we don’t have to explain anything among ourselves… If anyone has issues they wish to discuss, we can bring it up and hopefully resolve it.”

Following the catastrophe, Meanen was required to wear pressure garments over the scarring on his arms and hands during summer for protection. “I wore gloves in the summer, these medical gloves,” he shares. “Naturally, individuals who didn’t know me would give me a few odd looks. For a couple of years, I constantly wore long-sleeve T-shirts. Eventually, I thought: ‘Forget that, it wasn’t my fault.’”

He believes that his physical scars aided in his mental recovery. “This is merely my perspective,” he states, “but having physical injuries and the scars you bear … provide proof that you were there and involved, laying visible tokens of your experience. In contrast, some individuals bear no physical scars, only mental ones. I would think that’s significantly tougher for them.”

Meanen eventually married, had two children, ran a pub, and later worked as a school bus driver. Now retired, he continues to speak at oil companies, sharing his story and providing safety advice for offshore operations. He feels it’s crucial that the disaster be remembered, “hopefully to improve conditions,” he expresses, but also to respect “those who sacrificed their lives.”